In this episode: how one person’s life can mean death for another (the film Voor de meisjes (For the Girls); a racist who, at the end of her life, has to deal with a black caregiver (the novel Binnenrijm van bloed [Blood’s inner rhyme ); a hospital on rails (the documentary Salamatty Kazakhstan); and a film about a serious epidemic that leaves its mark on subsequent generations (Alpha).

Here you will find the PDF of this edition.

Comments, questions, tips, criticism, and praise can be sent to: scoop0329@gmail.com

Film

Voor de meisjes (For the girls), now in theaters

Moral dilemma: who lives, who dies?

Voor de meisjes (For the girls) by Mike van Diem—who previously made Karakter and De Surprise—could be interpreted as a (medical) moral thought experiment. Consider this: two couples who are friends have been sharing a vacation home in the Austrian Alps for years. When their teenage daughters are involved in an accident during a joint vacation, the apparent friendship quickly crumbles, and all kinds of hidden issues come to the surface. One daughter is left in a coma as a result of the accident and will never wake up, while the other has serious heart damage and will need a new heart. The situation really gets out of hand when the parents learn that one daughter can be saved, but only if the other, comatose girl is given up and her heart is ‘made available’. You’re right: a moral dilemma. In a controlled space, yes, because the action takes place, apart from the beginning and end of the film, more or less in one place and in a relatively short time, and is very much like a manipulative chess game in which pieces are sacrificed. Does it end in a draw or does someone win?

In any case, emotions run high: but perhaps a little differently than the viewer initially expects, because the parents are more exaggerated types than full-blooded characters. In one couple, she looks timid but is decisive (Thekla Reuten), and he is sloppy and unpolished: “I do something in offshore or something” (Fedja van Huêt). In the other couple, she is pretty and undisciplined (Noortje Herlaar), and he is rather polished and autistic (Valentijn Dhaenens). The doctors in the film are also somewhat stereotypical, although less grotesque than the parents sometimes are.

Nevertheless, the whole thing works like a charm thanks to the clever script and Van Diem’s crystal-clear staging, which makes optimal use of the natural environment—he could not have shot this film in the flat, built-up Netherlands. Van Diem has in fact written a well-made play in which (almost) every element and every twist has or acquires meaning.

In a wonderful interview in De Filmkrant, he explained how he did this. He also talks about how differently audiences react to his film. Some see it as a sardonic black comedy, but there are also people who leave the theater feeling sad.

You’ll have to see for yourself how it all works out for you. I saw one of the best Dutch films of recent years.

Henk Maassen

Novel

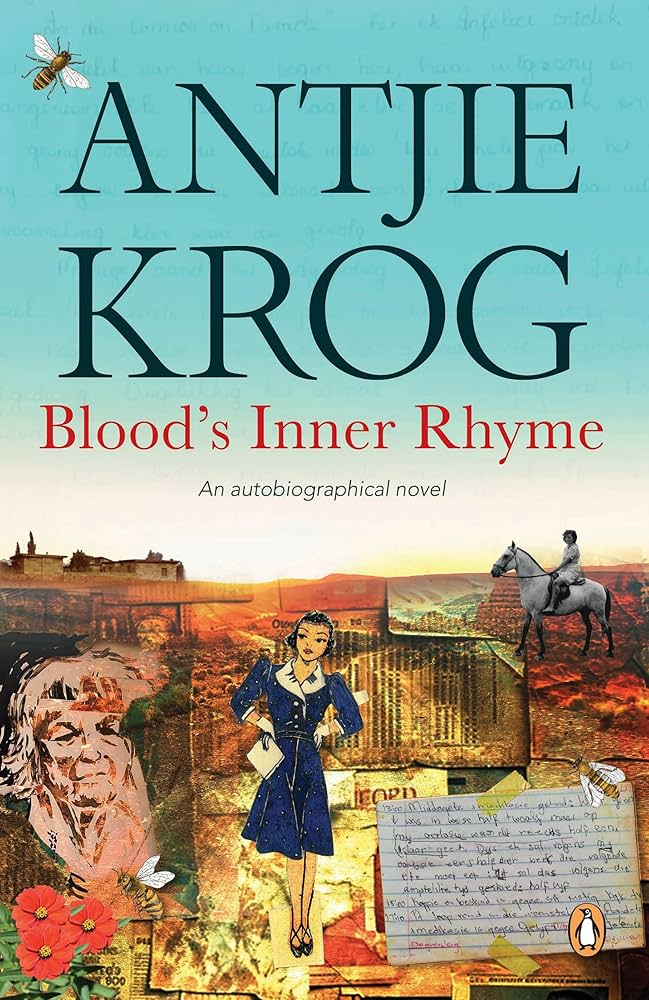

Binnenrijm van bloed (Blood’s Inner Rhyme), Antjie Krog,

Available in English on January 1, 2026

How to reconcile love and aversion?

Antjie Krog is one of South Africa’s best-known contemporary poets. Until now, she has only published prose occasionally, and now Binnenrijm van bloed (Blood’s Inner Rhyme), which was recently published in Dutch, has been added to that list. It is an autobiographical book. The poetic title already gives away something about the subject. An inner rhyme occurs when two words in a sentence rhyme, or in other words, when two words in a sentence belong together because of their sound. The word blood adds several dimensions to that inner rhyme. The book is about her relationship with her mother, to whom she is connected by blood. But at the same time, the word blood is also connected to race, which is certainly relevant in the South African context. Antjie is also connected to her mother by another bond: they are both writers. But Dot Serfontein, the mother, is a white writer from the apartheid era, and Antjie, the daughter, has distanced herself from apartheid. In the eyes of the apartheid regime, she was a traitor to her country.

Dot is in her 90s and in need of care. The nurse’s daily reports make that clear:

September 18, 2016

Pt is receiving oxygen. Pt’s hand is still swollen. Nurse will call doctor.

Pt is receiving medication and fluids.

Pt does not recognize anyone.

Stool is sparse and soft.

Her children do not all live nearby, so she needs to be cared for. This is done by black nurses, which Dot initially finds difficult to tolerate. Marlene van Niekerk has already written a novel about this: Agaath. In that novel, there could be a sense of revenge through the suffering of a white woman, once the boss, who is doomed to die of ALS, prolonging her life as long as possible through the perfect care of her black nurse, once her racial subordinate. But there is no mention of this in Antjie Krog’s book. Victoria, the main black nurse, helps her mother lovingly and adequately, and Dot also allows herself to be helped, albeit after a difficult start. But it is strange. At a family party on the family farm Elandspruit, where Dot is present with her nurse, Antjie notes: “It strikes me as a revelation: never before has our family at Elandspruit sat together like this, with a black person at the table. I look around, but everyone seems to be completely used to it.”

The cover states that Blood’s inner rhyme is an autobiographical novel. That is certainly true, but it belongs in a separate category. In addition to autobiographical memories, the book also contains letters to and from various people, nursing reports (almost always with a comment about Dot’s bowel movements), texts by her mother, both published and unpublished, poetry, interviews with those directly involved, photographs, images, and historical passages about the two Boer Wars around 1900. Sometimes it is not entirely clear who is speaking, but slowly but surely you get a better grasp of the text and then the struggle reveals itself, as the daughter’s gratitude and respect mingle with her incomprehension of her mother’s racism.

“As has been the case since my earliest childhood, I find myself once again in the stranglehold of utter admiration for her writing. God, that woman can write! But I am also touched by how she, who never hid her racism, was able to explore so impartially, so fearlessly, so boldly where her imagination and her writing talent would take her.”

Another interesting moment is when Antjie receives an award—it is the apartheid era—and a journalist asks her mother what she thinks about a traitor receiving this award. But Dot stands squarely behind her daughter. Dot is a mother to love and admire, but also a mother to hate, a difficult and headstrong person, that much is clear.

Dot’s departure also coincides with the sale of the family farm, which, although not really expropriated, it seems very much like it. The new political relations and corruption in South Africa are slowly creeping into the family.

I suspect that there are more people who find themselves in a similar situation when their father or mother is dying. Many parent-child relationships are filled with such love-hate feelings that are sometimes difficult to untangle. The sale of the children’s birthplace can also trigger deep emotions. This can lead to paralysis, but you can also, like Antjie Krog, try to untangle that knot of paralysis. She has succeeded brilliantly in doing so with this book.

Arko Oderwald

Documentary

Salamatty Kazakhstan, in theaters from October 9

An outpatient clinic on rails

Salamatty Kazakhstan (Healthy Kazakhstan) is an outpatient clinic on rails. The train travels non-stop for eight months of the year through 17 provinces, stopping at 121 stations and covering 18,000 kilometers to bring medical care to Kazakhstan. The mobile clinic reaches the most remote parts of this immense country and is open every day. Local residents can consult doctors for examination and diagnosis. The outpatient clinic on board is state-of-the-art and all major hospital specialties (including dentistry) are represented. Documentary filmmaker Ben van Lieshout traveled with the doctors and train staff for several months and filmed the patients they help.

We see how the train stops in villages with only a few hundred inhabitants, where the staff are always welcomed with a third-rate artist and a speech by a local dignitary. Then the patients arrive, in large numbers. Young and old and very old, and with a multitude of ailments: from an ingrown toenail, a sore tooth, and an outdated IUD to eye problems, prostate complaints, and severe heart failure.

In interviews, it becomes clear what motivates the doctors to be away from home for so long: they say they consider it important that everyone in their country has free access to medical care, but the fact that their work is well paid is also a motive that should not be underestimated. They accept that this means they have to be away from their often young children for long periods of time.

Van Lieshout captures it all with an eye for detail, often lingering on the faces of all these people. His film also emphasizes the working community of all those people on board the train and, in passing, gives an impression, but no more than that, of a country where time sometimes seems to stand still – Doctor: “Do you have diabetes?” Patient: “What is diabetes?” – but sometimes not at all: even in Kazakhstan, people use TikTok, Instagram, and WhatsApp.

Henk Maassen

Film

Alpha, now in theaters

Intergenerational trauma caused by infectious disease

Thirteen-year-old Alpha lives with her single mother and is going through puberty. When she comes home from a party with a tattoo, all hell breaks loose. Her mother, who works as a doctor in a hospital, thinks she has been infected with a virus that no one wants to talk about, but which everyone is terrified of, through a dirty needle. Her hospital is now full of patients who have been infected. Julia Ducournau, director/screenwriter of the film Alpha, was born in 1983 to two doctors, two years after AIDS first appeared, and it is clear that she was inspired by that disease. We know her as the filmmaker behind Raw and Titane, films in which she made no secret of her preference for body horror. Alpha is no exception: patients with the strange disease gradually turn into a kind of hard, marble statues.

Ducournau chooses this approach because she wants to tell more than just the literal history of AIDS. Her film aims to evoke the same fear she felt in the environment in which she grew up during the 1980s and 1990s. In an interview with her, she said: “What struck me most at the time, even more than the idea of the virus itself, was how every layer of society became infected with fear, and how that led to a certain group of people being excluded — instead of society facing up to the trauma and admitting that it affected everyone.” She shows the impact the disease had on society, using imagery that gives the past the look of photographs from that era. This contrasts with the often steel-blue present in the film. Because Ducournau also wants to show the intergenerational trauma caused by the AIDS epidemic, her film brings the past and present closer and closer together, until they seemingly converge. This sometimes leads to confusing timelines that, at a certain point, were no longer possible to untangle for this viewer, but it is not impossible that this is precisely Ducournau’s intention. Alpha is therefore typically a film that you should see twice.

The film’s point of view is, I think, that of Alpha, the pre-teen girl. Even the scenes from the life of her mother or the life of her uncle Amin, who became infected with the virus, can still be interpreted as Alpha’s version of them, even though she was not physically present. As a result, the scenes in the film ultimately function as “A Dream Within a Dream,” just as expressed in the poem of the same name by Edgar Allan Poe that she hears about during English class: “All that we see or seem/Is but a dream within a dream.”

But it wasn’t a dream; it was a terrible trauma packaged as a dream.

Henk Maassen