In this section we will describe all kinds of interesting medical-literary places in Europe. The section has started on June 21, 2025 and will appear every two weeks, alternately with Scoop. Older posts can be found below. Comments, questions, tips, criticism, and praise can be sent to Arko Oderwald: website@litmed.nl

October 11, 2025

On the spot – Lisbon – what remains

Here is the pdf

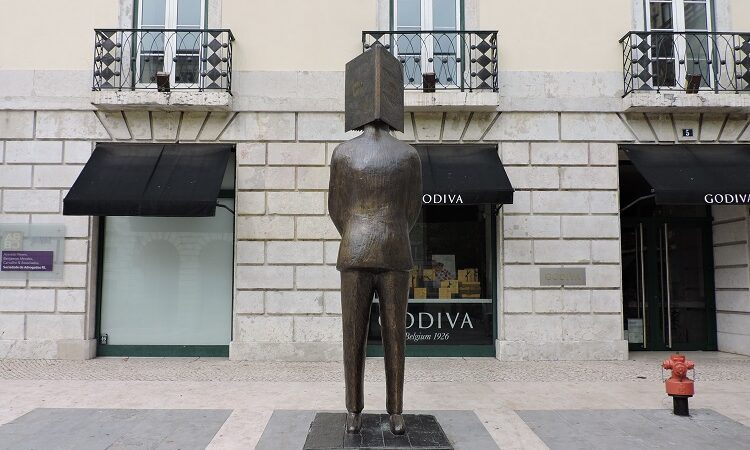

In eight episodes, we have reviewed all kinds of literary and medically relevant places in Lisbon. Although this collection can always be expanded later, in this – for now final – episode about Lisbon, we will briefly focus on a few places in Lisbon that are also worth visiting and – we will start with this – on two writers who repeatedly appear in the works of the writers already discussed: Luis de Camões and Eça de Queirós.

Writers

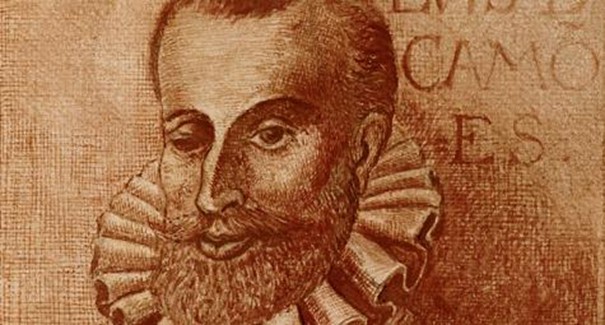

Luis de Camões

Every culture and every country has its own mythological figures. In the Netherlands we have William of Orange and Johan Cruyff, Portugal has Luis de Camões and Ronaldo. Luis de Camões lived from 1524 to 1580. He had a rather turbulent life, and since 1867 he has been depicted in the center of Lisbon as a warrior and a poet who was not always popular with those in power.

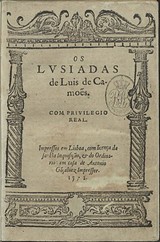

According to tradition, he died on June 10, which is now a national holiday in Portugal. People celebrate his turbulent life on that day. In 1548, he was banished from Portugal and went to Morocco, where he lost an eye. In 1553, he ended up in prison, and once released, he left for Goa, and from there he traveled on to Macao in 1555. There he wrote his masterpiece, Os Lusiadas. Every child in Portugal has read it at school. Here is a very small excerpt from Os Lusiadas.

I bid you farewell, my life! For

I already feel death living in my life.

Why, I ask, should I still strive for happiness,

If those who achieve the most lose the most?

But on this I give you my firm hand

That, even if my torment kills me,

Your memory will survive Lethe

And sail safely to the other side.

Honor without you brings tears to my eyes

Rather than rejoicing in anything else;

Better to forget them than for them to forget you.

Better that this memory cause them to suffer

Than that, by allowing your image to fade,

They be deemed unworthy of the glory of that sorrow.

Waters of the Mondego, benevolent

And gentle to my longing, where for a long time

I cherished hope, believed in deceit

And followed it, as if I were blind:

I now take my leave of you; but I am still bound

By the longing that guides me

And does not allow me to part from you:

The further away, the closer I find myself.

Even if Fate takes this prison

Of the soul to foreign lands, new songs,

To distant seas, storms and darkness,

The soul itself watches you from here

And flies on wings of swift desire

To you, O waters, to bathe in you.

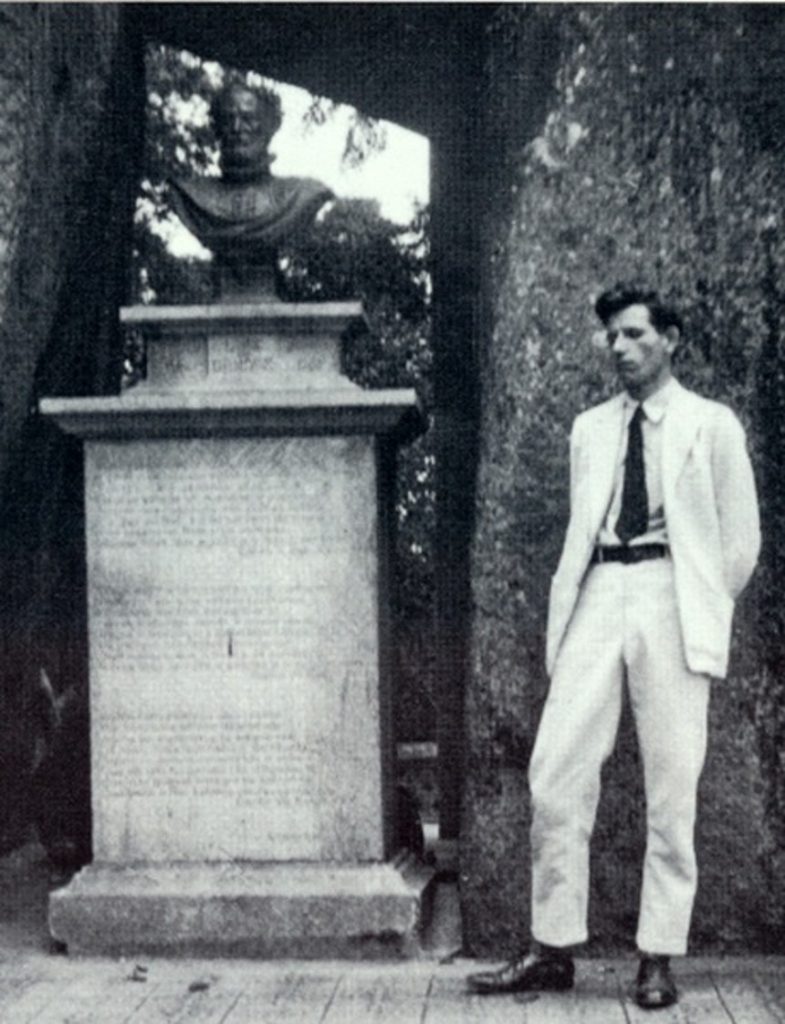

It is not difficult to see why Slauerhoff was so fascinated by Camões: the traveler and poet came close to him. No wonder he went to visit the famous cave in Macao.

Macao looks a little different now, by the way.

Slauerhoff wrote a number of poems about Camões, of which here is an example

Camões

He spent his youth in a remote castle

And served a court, spiritless, frivolous, and arrogant.

He fled, wildly yearning for a greater destiny,

Alone to the newly established States.

For his silence and uncertain shot

Despised by merchants and soldiers;

On board, in the fort, prey to the dull conspiracy

That he could not eradicate, only hate powerlessly.

Yet his dream persisted until its realization:

When he did not go to conquer strange wonderlands

With a mighty armada,

He wrought in the chilly twilight of the cave

Doomed poet, wanderer, and exile –

The heavy stanzas of the Lusiade.

(Grotto, Macao)

We owe it to the brave Luis de Camoes that Os Luciadas can still be read today. Shipwrecked off the coast, he had to swim ashore, but fortunately he kept the book above his head.

Once he arrived in Lisbon, a cold reception awaited him.

To my friends

Happiness, hoped for too long, always turns to sorrow.

When we first saw the landmark: Cintra’s hills,

Heitor was also carried to the aft deck

And slid into the sea from under the red-green cloth.

Then, right across the horizon, came the blue Tagus and

The brown hills receded, as the crow flies:

As if the fatherland opened its arms,

Wanting to carry us back to its heart.

No bonfires blazed in Lisbon.

A yellow flag flew from the old fort.

No pennants fluttered from the empty walls.

The fleet was kept at anchor, fearful of the plague.

After seven days in the city,

Unaccompanied by anyone, we went together

Like ghosts in broad daylight through strange streets,

No cheering crowds, no women waving from the windows.

At court, no one knew our names anymore.

The new states were hardly known;

The monarch, controlled by women and prelates,

Remained cold to Macao’s foundation, Goa’s fame.

I felt betrayed by seven years of work;

I had raised my Lusiade

In ship’s holds, caves, and hermitages, day and night,

Saved from fire and shipwreck like my wife.

To give it to the fatherland:

But where the enemy lies at the borders,

Where pestilence reigns, earthquakes threaten

The people are oppressed, monastery after monastery is founded,

Heretics are killed, the glory of discovery is silenced,

There is only scorn for the heroic poem.

He died in 1580 during a plague epidemic. He disappeared into a mass grave, but was later given a beautiful tomb (where he does not lie) in the Mosteiro dos Jerónimos in Belem, where we had previously visited the tomb of Fernando Pessoa.

“Here lies Camões, prince of poets of his time. He lived poor and miserable, and so he died.”

Ricardo Reis, as the character created by José Saramago, also honors Camões.

Ricardo Reis crossed the Bairro Alto and ended up back at Camões via the Rua do Norte, as if he were in a maze that kept leading him to the same place, to this half-nobleman and half-soldier, a kind of bronze d’Artagnan, crowned with a laurel wreath because he had managed to snatch the queen’s diamonds from the machinations of the cardinal at the last minute, whom he would later serve when times and politics had changed, but it would be good if our poet here, dead and therefore no longer able to serve, knew that the rulers, including cardinals, take turns or simultaneously make use of him whenever it suits their purposes. It is time to eat, the morning has been spent walking and exploring, apparently this man has nothing else to do but sleep, eat, walk, occasionally write a line of poetry, and even that with pain and difficulty, sweating over meter and rhyme, incomparable to the uninterrupted duel of our musketeer. Os Lusiadas alone has more than eight thousand verses, and yet this is also a poet, not that he boasts of that title, as can be seen in the hotel’s guest book.

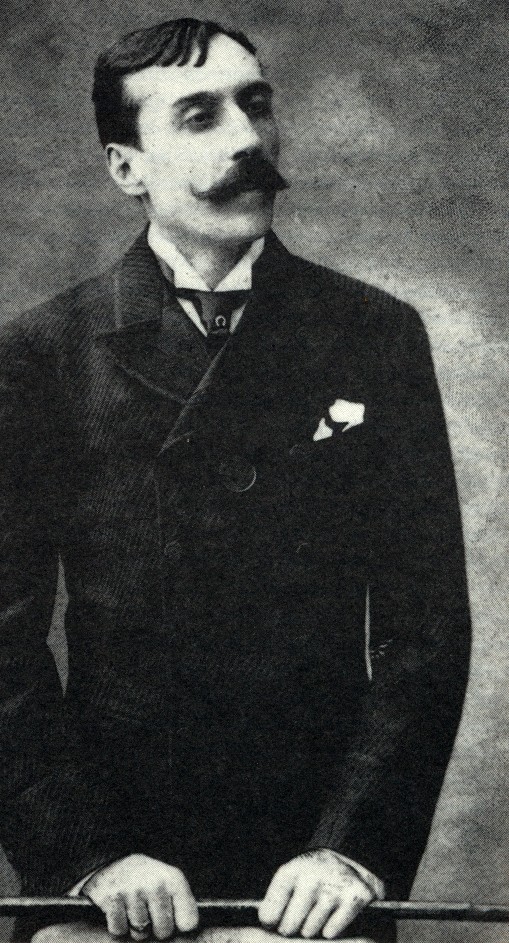

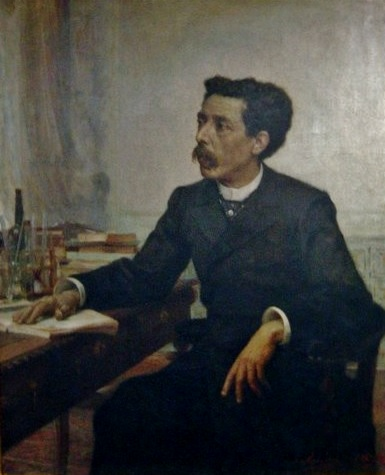

Eça de Queiróz

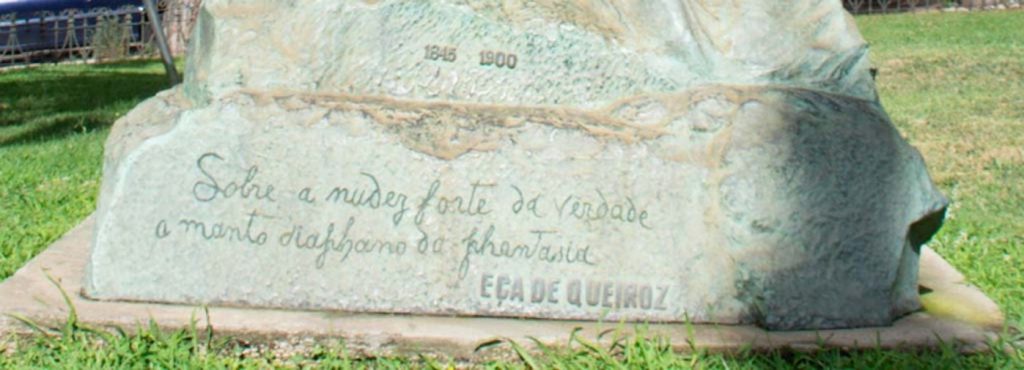

Ricardo Reis knows his classics, because he not only reflects on Camões, but also on José Maria Eça de Queriós, who lived from 1845 to 1900. He only came to live in Lisbon after completing his studies. He spent the first six years at Rossio, at no. 26. In Lisbon, he was a dandy-like intellectual who criticized the narrow-mindedness of his time. He, too, almost always moved in the vicinity of the statue of Luis de Camões, which cannot be a coincidence. The house of the main character in one of Eça’s novels was located on Largo do Quintela, and now there is a statue of the writer there.

About the raw nakedness of truth, the transparent cloak of fantasy,

is written under the statue. The naked woman must then represent the truth.

Saramago, as Ricardo Reis, also discusses the statue.

Reis pauses in front of the statue of Eça de Queirós, or Queiroz, out of respect for the spelling used by the bearer of the name, oh how different spellings can be, and a name is actually nothing, it is downright bewildering that these two speak the same language and one is Reis, the other Eça, probably the language chooses the writers it needs, uses them to express a small part of what it is, I wonder how we should live when the language has said everything and falls silent. The first problems are already beginning to arise, or no, they are not yet real problems but different, contradictory layers of meaning, stirred-up sediments, new crystallizations, for example, Over the solid nakedness of truth the diaphanous cloak of fantasy, the statement seems clear, clear and distinct, a child could understand it and repeat it flawlessly in a test, but that same child would understand and repeat another saying with equal conviction, Over the solid nakedness of fantasy the diaphanous cloak of truth, and this saying does give food for thought and pleasant fantasizing, naked and solid the fantasy, only diaphanous the truth, if the statements derived from their opposites became laws, what kind of world would we make of it, it would be a miracle if people didn’t go crazy every time they opened their mouths.

We walk away from the statue again. We eat a pasteis at Cister

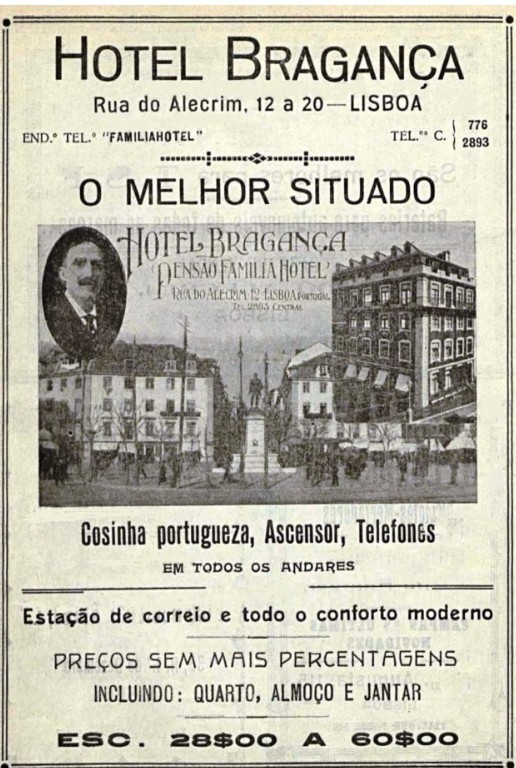

and finally end up at Largo do Carmo, where we can admire both the cathedral, destroyed in the earthquake, and the former Hotel Bragança, which is now the headquarters of the Guardia Nacional. This is where the Carnation Revolution took place. From here, we can descend to the Rossio again. There stands the statue of Pedro IV, a statue with a remarkable history. It was a statue of Emperor Maximilian of Mexico. In 1867, it was ready for transport to Mexico, but the emperor was executed. The Portuguese government took over the statue for next to nothing, added a beard (Maximilian did not have a beard) and placed it on a very high pedestal of 27 meters. No one noticed that this was not Pedro IV, the 28th king of Portugal and the first emperor of Brazil.

Quite a bit of Eça’s work has been translated into Dutch and English as well. Some say he is the Zola of Portugal, but that is only indirectly true. It is usually not medical-literary prose, but that should not be a problem.

Places

Aqueduct and Water Museum

Aqueduct address: Calçada da Quintinha Campolide

Reservoir address: Reservatório da Mãe d’Água das Amoreiras, Rua das Amoreiras

Museum address: Rua do Alviela

The greatest contribution to our health is undoubtedly the sewerage system and clean drinking water. In the second half of the 19th century, major works were undertaken to achieve this. This was also the case in Lisbon. First, there is the enormous aqueduct, the aqueduto das Águas Livres. The need for clean drinking water was already clear in the 18th century, and in 1731 work began on this waterway, with a total length of 58 kilometers. Part of this is the aqueduct over the Alcantara valley, which is 941 meters long and 65 meters high. The aqueduct was completed in 1748. The earthquake of 1755 destroyed much of Lisbon, but the aqueduct withstood it.

The aqueduct is also open to visitors. For a few euros, you can walk across the aqueduct. It is a bit disappointing that, somewhere just over halfway, you cannot continue and have to walk back. But on the other hand, if you could continue, you would be on the other side and the way back would not be so easy. Be sure to bring an umbrella, not only if it threatens to rain, but also to protect yourself from the sun.

The water then had to be collected somewhere, so basins were built for this purpose. One of the basins can be viewed in the Reservatório da Mãe d’Água das Amoreiras. The reservoir has a capacity of 5,500 cubic meters.

The history of the water can be found in the museum, but that is on the other side of the city.

Across the Tagus

Normally, you wouldn’t immediately think of crossing the Tagus. You can do so via the 25 April Bridge, but that’s probably not possible on foot. Another option is to take the ferry from Cais do Sodre to Casilhas, which takes 10 minutes. There you can hop on a (modern) tram, but that’s not really that interesting. It’s more fun to turn right immediately after arriving and walk along the Tagus. There is a whole row of ruins of houses there, where no one seems to live (but that’s not entirely true). Behind the houses is a fairly high wall. Be careful when walking, as there are holes in the road. It seems to lead nowhere, but turn left at the end and you will see a small bay with two restaurants.

It’s definitely worth eating here, but reservations are not easy to make, as emails are not answered. But if you succeed, you’ll have a beautiful view.

If you continue walking, you will come to a tower with an elevator. If the elevator is working, you can go up. The tower is connected to the hill by a bridge. There used to be a café there, where you could enjoy an espresso while looking out over Lisbon. Perhaps it is open again now. You can walk back along the top and you will end up back at the ferry.

You can also walk around the bottom of the tower, follow the Tagus River, and you will probably arrive at the restaurant that Herman de Coninck mentioned, at the foot of the Christ statue.

Tile Museum

Lisbon is the city of tiles, the azulejos. Many houses in Lisbon are covered with tiles. These tiles have a history that can be explored in the Tile Museum.

The Tile Museum is also the last topic we will mention about Lisbon. We may return here in the future, but for now we will conclude. Next time, not a city, but a person: Vincent van Gogh.

September 27, 2025

On the spot – Lisbon – Two novels set in Lisbon

Pascal Mercier – Night Train to Lisbon

Location: Kirchenfeld Bridge, Bern, Switzerland, and Lisbon

Cost: none

One of my favorite walks in Bern is to slowly walk down the covered Kramgasse and then the Gerechtigkeitsgasse. Just before the bridge over the Aare that leads to the famous bear pit, which fortunately is no longer a bear pit, you descend to the left of the road to the banks of the Aare. You can follow the road, but you can also take a covered staircase. Once you reach the bottom, you walk past houses that occasionally suffer from extremely high water levels in the Aare, which flows quite wildly here. Eventually, you will arrive at a road directly along the Aare and walk down to the Kirchenfeldbrücke. This bridge was opened in 1883, initially only for horse traffic and pedestrians. Now cars and trams drive over it, so the bridge has been reinforced several times. The bridge is 37 meters high.

It is not easy to see, but there are nets on the sides of the bridge to prevent people from jumping off.

And that possibility of suicide is the start of Pascal Mercier’s world-famous novel, Night Train to Lisbon. The main character is the eccentric classical languages teacher Raimund Gregorius, 59 years old.

The day after which nothing in Raimund Gregorius’ life would ever be the same again began like countless other days. He left the Bundesterrasse at a quarter to eight and walked onto the Kirchenfeldbrücke, which leads from the city center to the gymnasium. He did this every working day when there was school, and it was always a quarter to eight. When the bridge was closed once, he made a mistake a little later during Greek class. That had never happened before and never happened again. For days, the whole school talked about nothing but that mistake. The longer the discussion continued, the more people became convinced that they had misunderstood the teacher. Finally, that conviction also prevailed among the students who had been there. It was simply unthinkable that Mundus, as everyone called him, would make a mistake in Greek, Latin, or Hebrew.

On the bridge, a young woman seems to want to step over the railing. He speaks to her and she goes with him to the school, attends a class, and disappears again. On the bridge, she wrote a phone number on his forehead that she wanted him to remember. He knows she is Portuguese and goes to a bookstore, where he finds a book by a Portuguese doctor, Amadeu Prado. He reads it and is so intrigued that he immediately leaves everything behind and takes the night train to Lisbon. There he arrives at Santa Apolónia station.

The novels and poetry we have discussed so far are connected to Lisbon in their origins. But how important is Lisbon to Night Train to Lisbon? This question is not so easy to answer. Gregorius has a hotel in Lisbon, walks through Lisbon and takes the ferry to the other side of the Tagus. He takes the tram, among other places to Belem.

Gregorius rode Lisbon’s hundred-year-old tram back to the Bern of his youth. The tram car, which bumped, shook, and rang its bell as it rode through the Bairro Alto, seemed in no way different from the old tram cars with which he had ridden for hours through the streets and alleys of Bern when he was still allowed to travel for free. The same kind of lacquered wooden benches, the same bell cord next to the loops dangling from the ceiling, the same metal arm that the driver used to brake and accelerate, the workings of which Gregorius understood as little now as he had then. At some point, when he was already wearing the cap of a lower secondary school student, the old trams had been replaced by new ones. They made less noise and ran much more smoothly, the other students fought to ride in the new tram, and many were late for school because they had waited for one of the new cars. Gregorius hadn’t dared to say it, but it annoyed him that the world was changing.

He learns Portuguese very quickly, although there are also moments when he doesn’t understand a word. The latter is striking, because he can read the Portuguese book quite well without any knowledge of Portuguese.

As a book lover, he naturally also goes to bookstores, where he discovers Portuguese literature.

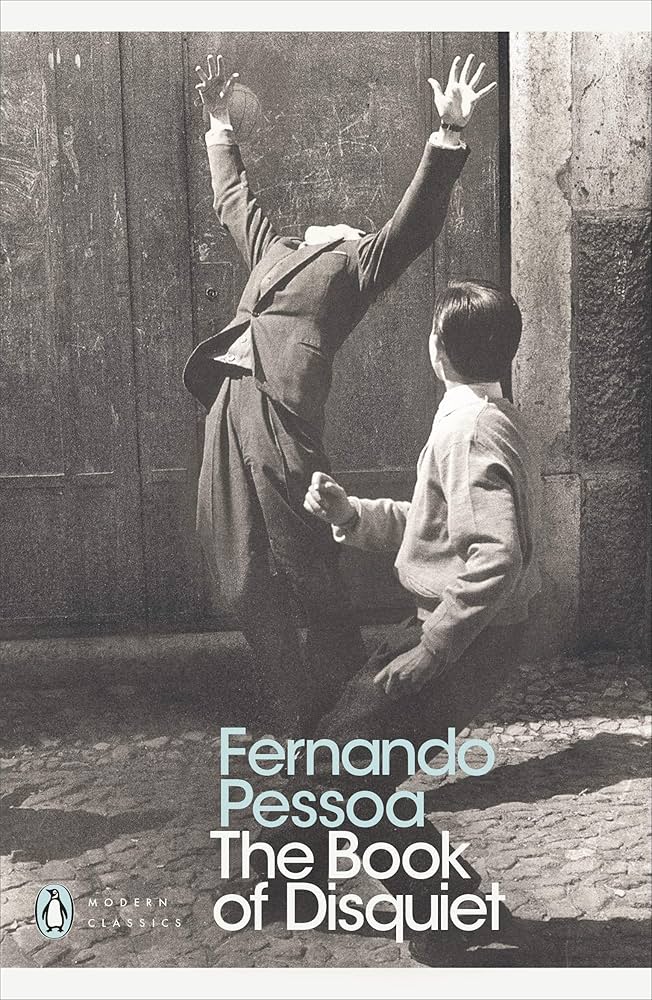

With both books under his arm, Gregorius walked to the other side of the store, where the literature was. Luis Vaz de Camóes; Francisco de Sá de Miranda; Fer¬näo Mendes Pinto; Camilo Castelo Branco. A whole universe he had never heard of, not even from Florence. José Maria Eça de Queirós, O crime do padre Amaro. Hesitantly, as if it were something forbidden, he pulled the book from the shelf and placed it with the other two. And then suddenly he was standing in front of it: Fernando Pessoa, O livro do desassossego, The Book of Disquiet. It was incredible, really, but he had gone to Lisbon without thinking that he was going to the city of the assistant bookkeeper Bernardo Soares, who worked on Rua dos Douradores and from whom Pessoa wrote down thoughts that were lonelier than any thoughts the world had ever heard before or since.

He gets to know Lisbon through books, that much is clear.

Gregorius stayed in the antique bookshop for a long time. Getting to know a city through the books you found there – that was how he had always done it. His first trip abroad as a student had been to London. On the boat back to Calais, he had realised that during the three days, apart from the youth hostel, the British Museum and the many bookshops in the vicinity, he had seen virtually nothing of the city.

Through a series of coincidences, he uncovers the history behind the book. He discovers where Dr. Prado lived, on Rua Luz Soriano near Praça Luis de Camões, and he discovers where Dr. Prado’s close friend still works, the pharmacy on Rua dos Sapateiros, in Baixa.

And finally, he learns about the Portuguese dictatorship, although the book about it is the only one he cannot find.

But does all this make this novel a Lisbon novel? That is debatable. For example, Lisbon is not described in detail anywhere. The two streets mentioned above are only mentioned by name. No further description is given. For example, they are very narrow streets, which certainly does not quite match the impression of the doctor’s house. Gregorius stands opposite both houses, watching from a distance, which is impossible because the streets are far too narrow. But anyway, it is not so important for the story whether the description corresponds to reality.

We don’t really learn much about the Portuguese dictatorship, which plays an important role in the book. My friend Inez from Lisbon even completely disqualifies the novel on this point. The main criticism is that the dictatorship is presented primarily as a problem of the past, whereas, certainly at the time the story takes place, that was definitely not the case. That is why Saramago left Portugal, precisely at the time this novel takes place.

Lisbon is therefore not decisive as Lisbon, but as a foreign city.

Prado would sit on the steps of his school and imagine what it would have been like to lead a completely different life. Gregorius thought about the question Silveira had asked him and to which he had given the headstrong answer that he had lived the life he wanted. He noticed that the image of the doubting doctor on the mossy steps and the question of the doubting businessman on the train had triggered something in him that the safe, familiar streets of Bern could never have triggered.

Night Train to Lisbon is, after all, essentially the story of a boring 59-year-old bookseller and teacher who suddenly asks himself whether this life is indeed all there is. In Prado’s book, who is not only a doctor but also very philosophical, he reads the following:

Of the thousands of experiences we have, we mention at most one, he quoted. ‘Among all those unspoken experiences are also those hidden ones that unnoticed give our lives their shape, their color, and their melody.

He breaks free from his ironclad routine in Bern and, without a plan, goes to a strange place, Lisbon, in search of those other experiences. But Lisbon could just as well have been Tangier, or Barcelona, or Istanbul, as long as it was strange.

There comes a moment in the novel when, again on a whim, he takes the plane to Bern.

He had returned because he wanted to be back where he knew his way around. Where he didn’t have to speak Portuguese, or French, or English.

But then he discovers that he is now also alienated from Bern, and he quickly returns to Lisbon and puts the last pieces of the puzzle of Dr. Prado’s book together. This brings him some peace.

On the tram to Belém, he suddenly noticed that his feelings for the city were changing. Until now, the city had been solely the place where he conducted his investigations, and the time that had passed had been shaped by his need to find out more and more about Prado. Now, as he looked out of the tram window, the time during which the tram carriage creaked and groaned as it trundled along belonged entirely to him; it was simply the time during which Raimund Gregorius lived his new life. He saw himself standing at the tram depot in Bern again, asking about the old tram carriages. Three weeks ago, he had felt like he was riding through his childhood in Bern here in this city. Now he was riding through Lisbon and only Lisbon. He felt something deep inside him change completely.

So you could say that the night train to Lisbon leads to soul-searching in Lisbon, that the novel revolves around Raimund’s soul-searching and that Lisbon functions as the strangeness that is necessary for this.

Erich Maria Remarque – That Night in Lisbon

What applies to Night Train to Lisbon applies even more strongly to this novel by Erich Maria Remarque. Although, the novel is set in 1942. Dictatorial Portugal was neutral to a certain extent and served as a port of departure for boats to the free world. There were many refugees in Lisbon, but also Nazi Germans and Allies. This gave Lisbon a unique position in Europe, and in that sense Lisbon is indispensable to this novel.

The main characters in the novel are a man who has two tickets for the crossing to the United States and a man who is desperately looking for tickets. They meet, and the man with the tickets says he will give them to the man without tickets if he is allowed to tell his story. That takes a whole night. The men sit in a café that is open all night and drive and walk there.

We drove around the theatrical backdrop of Praça do Comercio and a little later ended up in a maze of stairs and alleys leading upwards. I didn’t know this part of Lisbon; as always, I mainly knew the churches and museums – not because I loved God or art so much, but simply because they didn’t ask for your papers in churches and museums. To the Crucified One and the masters of art, you were still a human being—not an individual with questionable identification papers.

We got out and walked up the stairs and through the winding streets. It smelled of fish, garlic, night flowers, dead sun, and sleep. In the light of the rising moon, St. George’s Castle loomed beside us out of the night, and the light cascaded down the many steps like a waterfall. I turned and looked at the harbor. Down below lay the river, and the river was freedom, it was life, it flowed into the sea, and the sea was America.

The man who sold the tickets tells how, as a person wanted by the Nazis, he tried to get his wife out of Germany. He is pursued by his wife’s brother, a fanatical Nazi. After wandering through Germany, Switzerland, and France, he manages to escape his brother and flee with his wife to Spain, then on to Portugal.

In the café where the men are sitting, there are also English and Germans, who get into an argument with each other. Halfway through the story, the men decide to go to another café.

We went outside and the night was beautiful. There were still stars in the sky, but on the horizon the sea and the morning were already in their first blue embrace; the sky had become higher and the smell of salt and blossom was stronger than before. It was going to be a clear day. During the day, Lisbon has something naive and theatrical about it that enchants and captivates you, but at night it is the fairy tale of a city that descends towards the sea in terraces with all its lights on, like a festively adorned woman bending over her dark lover.

There, the man with the tickets tells us that all this time his wife was suffering from terminal cancer. She kept it hidden from him for a long time, but in the end she had to tell him. She makes it to Lisbon, but there she dies. That is why he wants to give his tickets away to someone who needs them more; he wants to join the Foreign Legion.

It is a poignant and sad story of escape, of which many have been told in literature. And this story takes place in Lisbon, but at the same time, the above two quotes are the only ones in which Lisbon is described. Nevertheless, with some exaggeration, these two quotes give a richer picture of Lisbon than all the quotes from Night Train to Lisbon that describe Lisbon. In that novel, Lisbon functions primarily as a symbol of strangeness. It could have been any other city. Unlike in Mercier’s story, Lisbon is necessary for Remarque’s story. In 1942, Lisbon was one of the few cities in Europe where refugees could still escape Europe. But that said, Lisbon is otherwise virtually absent from the novel.

Of course, this is a somewhat black-and-white conclusion, but not illogical in my opinion.

Arko Oderwald

Here is the pdf

September 13, 2025

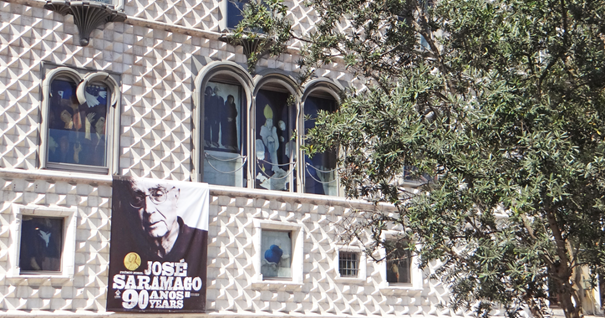

On the spot – Lisbon – José Saramago

Location: R. dos Bacalhoeiros, Fundação José Saramago

Cost: 4 euros.

We are standing near the Tagus River on R. dos Bacalhoeiros, in front of an olive tree. That olive tree is not here by chance. Beneath that tree lies José Saramago, or at least his ashes. Next to the tree is the text

Mas não subiu para as estrelas s’e a terra pertencia, loosely translated as:

But he did not ascend to the stars if the earth belonged to him

The tree stands in front of the house that houses the Fundação José Saramago, a biographical museum dedicated to José Saramago. The house is a restored 16th-century building, the Casa dos Bicos. The museum provides a fascinating insight into the life of José Saramago.

Lisbon was the city of Nobel Prize winner Saramago, although he was not born here. However, the cities in his novels are not always directly traceable to Lisbon. I think there is a reason for this, because Saramago was not on speaking terms with those in power. Born in 1922 and deceased in 2010, he experienced both the dictatorship and the post-dictatorship era. Unlike Lobo Antunes, Saramago did not come from a wealthy family, but from a family of day laborers. He worked as a mechanic and later as a journalist. His first novel was not a success, and then there was a 20-year hiatus. It was not until 1980 that he became known as a writer with a novel about the harsh life in the countryside, in which his communist sympathies clearly resonate. This novel also saw the first appearance of Saramago’s typical style. There is little white space on the page, the paragraphs are long, the dialogues are written in continuous lines, with only a comma and a capital letter indicating a change of speaker. Punctuation is unusual. This creates a compelling rhythm.

Where to, but the answer came earlier, still hesitant, uncertain, To a hotel, Which one, I don’t know, and at the same moment he said that, I don’t know, the traveler knew what he wanted, with such firm conviction that it seemed as if he had been thinking about that choice throughout the entire journey, One that is close to the river, down here, Then only the Bragança comes into consideration, on Rua do Alecrim, I don’t know if you know it, I can’t remember the hotel, but I know the street, yes, I lived in Lisbon, I’m Portuguese, Oh, you’re Portuguese, I thought you were Brazilian, the way you talk, Is it that noticeable, Well, noticeable, you can hear it, I haven’t been to Portugal for sixteen years. That’s a long time, a lot has changed in that time, and with those words the driver abruptly fell silent.

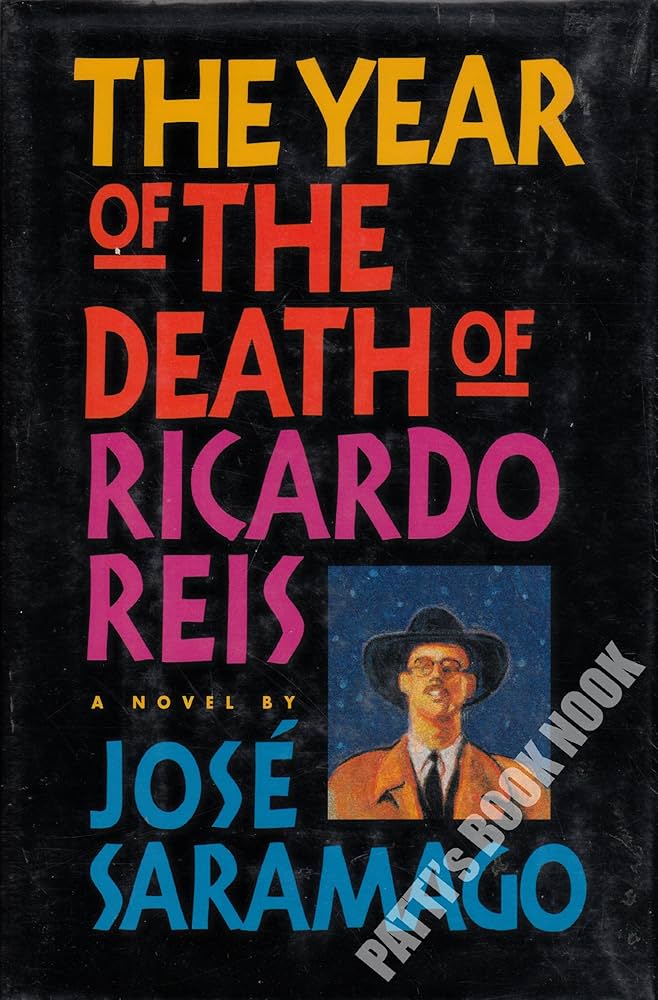

(The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis)

And finally, there is a strong magical realism in many of his novels. The latter may also provide a clear reason why his novels feature cities that resemble Lisbon, but are not Lisbon. His novels are often parables with a general message and can therefore take place anywhere.

As mentioned, Saramago and those in power did not get along. This was true not only during the dictatorship, but also after it. Although this dictatorship ended with virtually no bloodshed, the Carnation Revolution, it also ended without anyone being held accountable. The executioners of the dictatorship were not punished. No bloodshed sounds good, of course, but much of the suffering went unpunished and thus had the chance to fester beneath the surface. Saramago therefore left Lisbon and Portugal and went to live in Lanzarote (Spain).

His most famous novel is undoubtedly Blindness.

There is a sudden epidemic of acute blindness. People move through the city in rows, holding on to each other, as in Breugel’s painting.

Pieter Bruegel: The Parable of the Blind. Museo di Capodimonte, Naples.

It soon becomes clear how thin our layer of culture is in the face of a threatening infectious disease. Everyone is left to fend for themselves. The power of the story lies in the idea that something like this could happen to any of us, not just the people of Lisbon. But an epidemic is not a magical realist element, as the COVID period made clear. During our COVID period, novels that had already described such a scenario were often mentioned, with Albert Camus’ The Plague scoring highly. But Philip Roth’s Nemesis comes closer, and Blindness also comes close when it comes to the actions of the government, even though Saramago’s is much more merciless and violent.

The magical realism of Saramago’s books is sometimes truly implausible, yet convincing. In The Cave, Plato’s cave is discovered during the construction of a supermarket, and in Death with interruptions, Death stops doing his job. People in an unspecified country no longer die. Before you start cheering, remember that people who are dying still suffer, but they no longer die. If these people are taken across the border, they do die. Life insurance companies are happy because they don’t have to pay out. The church considers it a scandal, because the church exists because of the promise of an afterlife, eternal life, whether that be heaven or hell.

Saramago writes parables with a general message, which is why explicit references to Lisbon are unnecessary. That is to say, most of the time. I previously wrote about Pessoa and Saramago’s novel The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis. In that novel, the real Lisbon does play a role.

Ricardo Reis comes to Lisbon after the death of Fernando Pessoa. Reis is one of Pessoa’s heteronyms. He is a Brazilian doctor who writes poetry. Upon arrival in Lisbon, he takes up residence at the Hotel Bragança, Rua do Alecrim.

The hotel is still there, but it now has a different name. From there, Reis walks through the neighborhood, with Praça de Luis Camões as its center. Eventually, he finds work as a doctor on that square. Reis stays at the hotel for a while, but then moves to Rua de Santa Catharina, near the mirador of the same name.

A few minutes later, Ricardo Reis was standing on Alto de Santa Catarina. Two old men were sitting side by side on a bench looking at the river. They turned around when they heard footsteps, and one said to the other, “Gosh, that’s the guy who was here three weeks ago.” He didn’t need to provide any further details; the other immediately added, “The one with the young lady.” Many other men and women have passed by or stopped here in the meantime, but the old folks know exactly who they are talking about. It is a mistake to think that you lose your memory with age, that only the oldest memories remain intact and gradually resurface, like hidden tree trunks when the water recedes after a flood. There is one terrible memory in old age, that of the last days, the last image of the world, the last moment of life.

It is not far from the hotel. Via Praça de Luis Camões, we follow the yellow tram into Rua do Loretto. After a while, on our left, we see the upper station of one of Lisbon’s three cable cars. We already encountered one of the other cable cars in the first episode. The third cable car recently had a disastrous accident. Just after the cable car, turn left onto Rua Marechal Sandanha. At the end of the street is the Pharmacia museum, a museum about the history of pharmacy in Portugal. It is not a spectacular museum, but it does provide a solid overview.

Next to the museum is the Pharmacia restaurant, serving delicious Pharmacia-style food, with lots of pharmaceutical cabinets in the dining room and pharmaceutical accessories on the tables. Be sure to make a reservation in advance (and hope you get a reply).

Then take a look at the view from the Mirador Santa Catharina. This is where Ricardo Reis comes to live, and here too there is a Luis de Camões view: a statue of a mythical hero from his work: Adamastor

From here, it’s not far to Rua da Esperança, where Saramago lived at number 76. Saramago regularly ate at the Varina da Madragoa restaurant, Rua das Madres 34.

We are almost at the end of our Saramago walk. But to honor his first novel, which is set in the Alentejo, we are going to have dinner at Casa de Alentejo. From Praça Santa Catharina, we walk back up and turn right at the top, once again to Praça de Luis Camões. We walk straight ahead and at Café Brasilia, where Fernando Pessoa still sits, we enter the metro and exit at Baixa. Turn left towards Rossio and then walk past the Teatro Nacional on the right, before turning into Rua das Portas de Santo Antão. Casa de Alentejo is at number 58.

The Casa de Alentejo is not particularly striking from the outside. Anyone looking for a restaurant would probably walk right past it. But once inside, that changes. It looks like a very old Moorish building.

But that’s all fake. The building dates from the late 17th century, but was completely renovated in the early 20th century to its current state. It used to house a casino. In 1939, it became a cultural center for the Alentejo region, and it remains so to this day. It is a conference center, a restaurant, a café, and a sales point for artistic products from the region.

Above, we see the conference hall. In addition, there is excellent food in an old dining room with many tiles on the wall.

Be sure to make a reservation in advance, as it is a popular restaurant.

Here you can find the pdf

Arko Oderwald

August 30, 2025

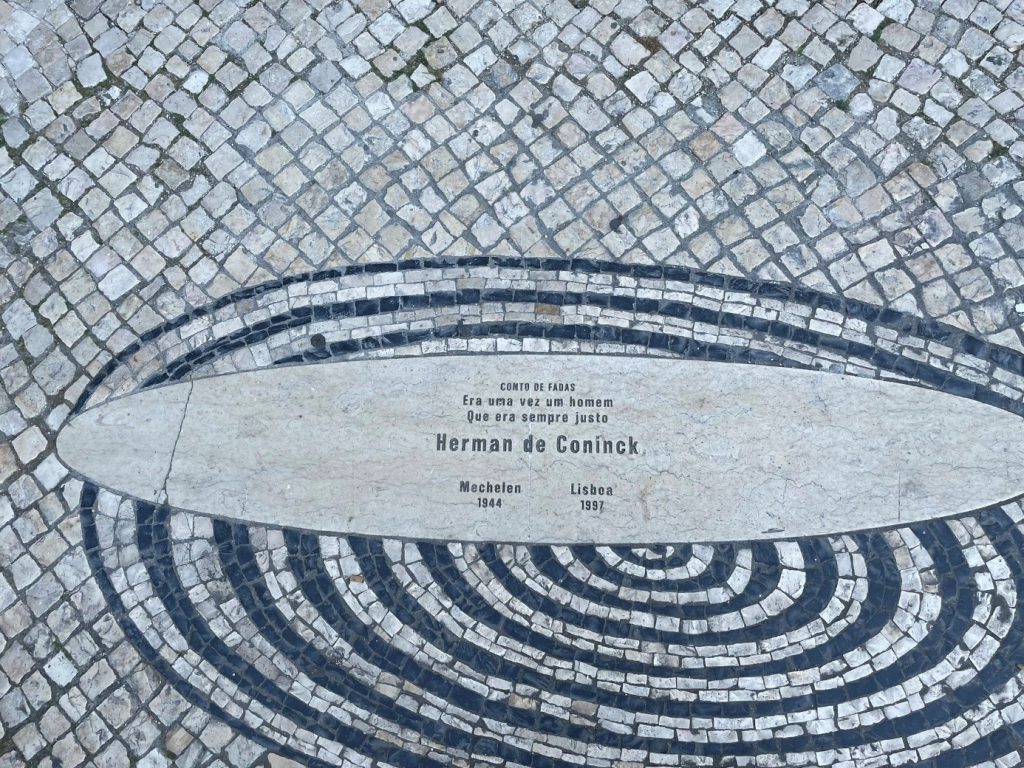

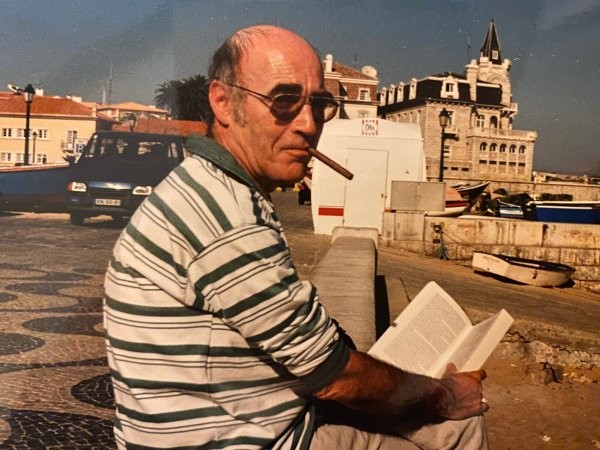

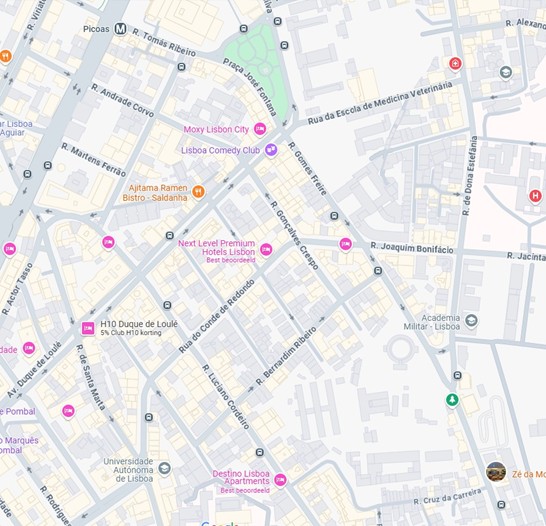

On the spot – Lisbon – Herman de Coninck

Location: R. Marquês Sá da Bandeira 74, 1050-165 Lisbon

Cost: free

How to get there: Metro Azul (blue line) station Praça de Espanha or São Sebastião.

Warning for the non-Dutch reader: As you know, this is originally a Dutch side, so now and then you will stumble upon some very Dutch, or, in this case, Flemish content. This episode of on the spot is about a famous Flemish poet. This may give some problems with the translation of his poems, but we hope you still enjoy it.

R. Marquês Sá da Bandeira is not exactly an appealing street in Lisbon. For a tourist, there seems to be nothing to see here. Hidden from view in the photo, to the left of the road is a long wall that forms the boundary with the Jardim da Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, the beautiful garden of the Gulbenkian museum, so you might walk down this street to visit the garden or the museum.

What may catch your eye in the photo is the small table with chairs to the right of the green extension of the restaurant. They are standing right on top of a memorial stone. And it is this memorial stone that will prompt some people to walk down this street.

On May 22, 1997, Herman de Coninck (Mechelen, 1944) died here on the sidewalk of R. Marquês Sá da Bandeira in Lisbon of a massive heart attack. He was only 53 years old and on his way to a literary conference. Under the auspices of the Dutch Foundation for Literature, an event was held in Lisbon from Wednesday 21 to Sunday 25 May to promote ‘Literature Contemporanea da Flandres e dos Paises Baixos’

Other Dutch writers, such as Hugo Claus, Anna Enquist, and Connie Palmen, were present when De Coninck died here, on the sidewalk.

From left to right: Tessa de Loo, Magda van den Akker, Herman de Coninck, Gerrit Kouwenaar, Margriet de Moor, Adriaan van Dis, Anna Enquist, Connie Palmen, Hugo Claus, Mirjan van Hee, behind her Gerrit Komrij.

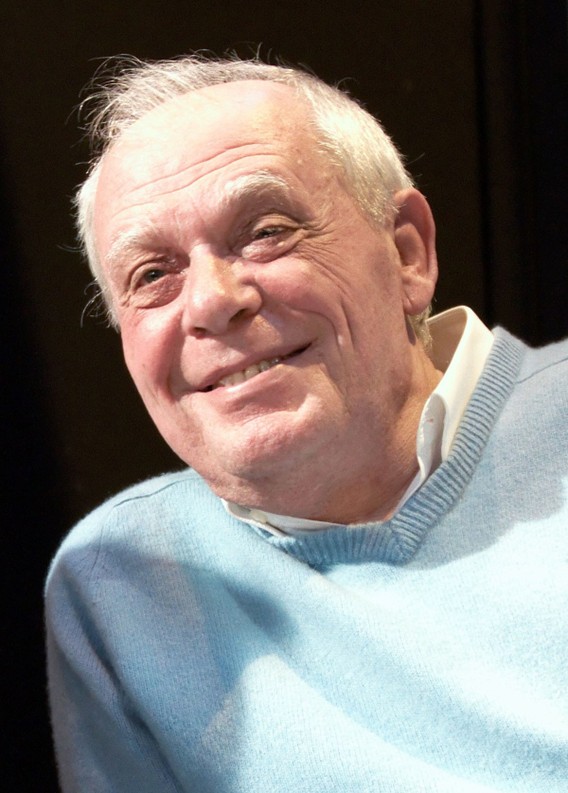

Rutger Kopland, a good friend and Dutch poet (and psychiatrist), who was not in Lisbon at the time, wrote

“Postcard of a Greek Island.”

Herman, I wanted to write you a card,

a silly postcard with a joke

about, well, you know what,

but I heard you had already died

before I could think of a joke.

I’m still alive, our conversation isn’t over,

but I’m living these last days bent over words

that I cross out, write down again—

What were we talking about, where

had we left off, without expecting death

you don’t write poetry, we

agreed heartily,

poetry was happiness, the happiness of finding a few words

that wanted to belong together for a short instant

and before death came to take us away,

a joke, a carefully concealed joke

about death, crossing it out and writing it down again,

that would be poetry.

So I will never see you again.

These days I live bended, for all that,

for that shy body, that melancholy head

with which you spoke, for all that

gets buried alive,

I mean, I live bent over that card,

you know, with a sea that is far too blue,

the sky that is far too blue:

Happy days in Greece.

De Coninck was a much-loved Flemish poet who wrote recognizably and crystal-clear about everyday things and about major themes such as love and death. That makes his poetry timeless. In literary jargon, he belonged to the “new realists,” but he would probably have laughed at that himself, as a poet of paradoxes, reversal, negation, and disappearance.

[…]

Perhaps I learned it from my mother.

‘Son, you know,’

she said when I got married.

It took me a long time,

volumes and wives

to say so little.

To unlearn the funny, then

the grumpy, and finally

come home in the few.

From love that was pliable onto the reliable

From: Fingerprints

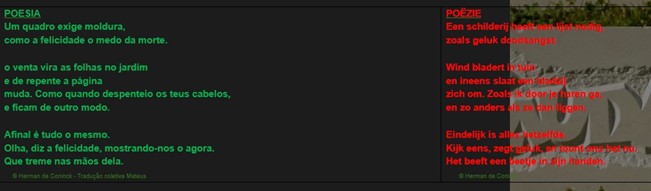

His work was also (partly) translated into Portuguese.

Poetry

A painting needs a frame

like happiness needs fear of death

Wind rustles in the garden

and suddenly a page

turns. Like when I run my fingers through your hair

and it looks so different afterwards.

Finally, everything is the same

Look, says happiness, and shows us the present.

It is trembling slightly in his hands.

In addition to his extensive oeuvre of poems, after his death, Onder literatoren (Among Writers) was published, a collection of his interviews with other writers, such as Paul de Wispelaere, Rutger Kopland, Gerard Reve, and many others. These interviews were from his time as a journalist for the Flemish magazine Humo. He would later leave Humo and found the Vlaams Wereldtijdschrift (Flemish World Magazine).

A brick-thick book of letters was also published, entitled Een aangename postumiteit (A pleasant posthumity), which reads somewhat like a biography of the years 1965-1997. The following fax to his wife is also included in that book

To Kristien Hemmerechts

Wednesday night, half past one May 22, 1997

Poes,

It’s nice here and the people are nice—but I miss you. I don’t have anyone here to say “remember…” to.

Tonight we had a nice dinner in a new neighborhood, a kind of Lisbon South, on the Tagus River, under a gigantic (xxx) Christ statue across the river. An old harbor warehouse converted into a restaurant. Afterwards we had a drink in what seemed like a terribly dirty neighborhood, in a kind of ground-floor loft: beautiful

Tomorrow morning I have a short interview in English about my poetry for the newspaper. I’m curious to see how it turns out. On Sunday evening, Veerle Claus might be able to pick us up from Zaventem.

Sweetheart, I love you and I miss you. Kisses.

Herman

This is a fax written on Wednesday night, May 21/22, and sent from Lisbon at 10:06 a.m. (local time) on Thursday, May 22, shortly before his death.

The giant Christ statue Herman refers to here is not in Lisbon, but in Almada. Dictators cannot think big enough, and this statue, commissioned by the dictator Salazar, is no exception. Including the pedestal, it is 75 meters high, and the statue itself is 28 meters high. Big enough to keep an eye on Lisbon and to be clearly seen from Lisbon. Not original, by the way; the original is in Rio de Janeiro.

It is an interesting image, though, the 25 April bridge, commemorating the revolution that overthrew the dictatorship, in one image with Salazar’s legacy.

Back to Herman de Coninck. In 2017, a real biography was published, ‘Toen met een lijst van nu errond’ (Then with a list of today around it). However, the most poignant book about Herman de Coninck is and remains ‘Taal zonder mij’ (Language without me), written by his wife Kristien Hemmerechts, in which she searches for and analyzes the autobiographical traces in his poems.

So if you do visit the museum and the garden, take a moment to pause in front of this memorial tile and let the treasure of language that ended here sink in.

Aafke de Groot and Arko Oderwald

Sources:

Hugo Brems (ed.) Herman de Coninck. De gedichten I en II. De Arbeiderspers, 1998

Christien Hemmerechts. Taal zonder mij. Atlas, 1998

Thomas Eyskens and Piet Pyriens. Onder literatoren. De Arbeiderspers, 2022

Annick Schreuder (ed.) Een aangename postumiteit. De Arbeiderspers, 2004

Thomas Eyskens. Toen met een lijst van nu errond. De Arbeiderspers, October 2017

Rutger Kopland. Kaart van een Grieks eiland. From: Tot het ons loslaat, van Oorschot, 1997.

Here is the pdf

August 16, 2025

On the spot – Lisbon – António Lobo Antunes

Location: Hospital Miguel Bombarda

How to get there: Metro yellow line, Picoas station.

Cost: free

We have just stepped out of the metro at Picoas station on the yellow line. The meeting point is the kiosk. This is fitting, as the history of kiosks in Lisbon is partly intertwined with the history of the writer who is the focus of this article: António Lobo Antunes.

The Quiosques can now be found everywhere in Lisbon. There are about 70 of them scattered throughout the city. The first kiosk is said to have opened in 1869. They come in all colors and sizes, but they all have six sides and a dome that refers to the Moorish period in Lisbon, which lasted almost 700 years. Most are green, like the one in the photo above, the kiosk near the statue of Camões. You can get coffee, wine, and snacks—both savory and sweet. Around 1930, Salazar and the dictatorship came to power. Because the kiosks led to gatherings in the streets—even today there are often long lines—they were closed by order of Salazar. The dictatorship disappeared in 1974. In 2009, the Quiosques were revived, and with great success.

The fact that the dictatorship banned the kiosks was only a small blip in the history of the Portuguese dictatorship. Virtually no Portuguese writer was able to escape this dictatorship, not even António Lobo Antunes. Lobo Antunes is a doctor and was forced to work in Angola and Mozambique, two former colonies of Portugal. After his return to Portugal, he became a psychiatrist.

His novels often deal with the history of Portugal before and after the Carnation Revolution. Examples include Fado Alexandrino and Sermon to the Crocodiles. Later, he wrote in a more general sense about the human condition.

We are here at this kiosk

to take a look at the hospital where he was a psychiatrist and about which he wrote a novel. We are in a part of Lisbon with modern buildings, not very attractive.

We walk into R. Tomás Ribeiro. Soon we arrive at a park on Praça José Fontana. On the other side of the park is the Liceu Camões, founded in 1910/11, which was innovative in that it had a gymnasium. Mens sana in corpore sano. We follow R Gomes Freire and after R. Bernardim Ribeiro we walk at the bottom of a hill with a wall and a high fence on top of it. Above it is the Hospital Miguel Bombarda. Running away is not only forbidden there, but also virtually impossible. It was a psychiatric institution.

Miguel Bombarda was a psychiatrist and republican. Born in Rio de Janeiro in 1851, he was killed by a patient in 1910, two days before a revolution he had fought hard for brought down the last Portuguese king.

This psychiatric hospital is named after him. Lobo Antunes came to work here. He describes this in one of his first novels.

In Knowledge of Hell from 1980, a psychiatrist travels alone from his vacation spot in the Algarve back to Lisbon. The next day, he has to return to work at the psychiatric institution. His wife has left him and taken their two daughters with her, but that does not prevent him from occasionally talking to one of his daughters in the back seat. When he once took her to the psychiatric institution, she refused to go inside because it was too scary.

As he drives, all kinds of memories come flooding back of the horrors of his (forced) time in Angola during the war, his failed marriage, and his work as a psychiatrist. The memories merge into a massive indictment, but also into frustration about his own inability to deal with it in a constructive way.

The institution admits people who are dangerous to themselves or others, but also people who are completely harmless. Almost all of them are treated in the same way: with neuroleptics injected into their buttocks to keep them calm.

The original Portuguese title contains the word inferno, and it is a pity that this word is missing from the Dutch title, because the novel describes hell. And for Antunes, that hell is mainly in the institution and not in the war in Angola. A quote from this novel:

And it was only in 1973, when I arrived at Hospital Miguel Bombarda to begin a long journey through hell, that I realized that night had indeed left the city, that it had withdrawn from squares and cemeteries and streets and parks and crept into the corners of the wards of that hospital, just like bats, in the ceiling lamps and the dilapidated medicine cabinets, in the electroconvulsive therapy machines, in the buckets of bandages, the boxes of syringes, until the patients return silently from the dining room and crawl into their threadbare beds, after which the nurse presses the light switch and that light spreads the disgusting felt of its wings, the disgusting, sticky felt of its wings over the men, who stare at it with uncontrollable revulsion from between the sheets. The night that was leaving the city lay on the bent face of the patient who had hanged himself behind the garages, whose broken sneakers swung slightly at the height of my chin, lay in the deaths I recorded when I was on duty and pressed the ice-cold diaphragm of my stethoscope against breasts that were motionless like boats that had finally moored, lay

in the distraught features of the living who were locked up between the walls and bars of the asylum, in the dust in the courtyards in summer, in the facades of the houses around. In 1973, I had returned from the war and knew everything about the wounded, about the cries of the wounded on the road, about explosions, gunshots, mines, about bellies torn to pieces by the explosion of an ambush, I knew about the wounded and murdered babies, knew about spilled blood and homesickness, but I had been spared hell.

This quote already shows the great evocative power of Lobo Antunes’ style. That style has since developed into a highly recognizable and unique poetic way of writing prose. If you like it, and that is by no means everyone, each new book of his is a feast. Polyphony, multiple voices alternating with each other and playing with time, is characteristic of his novels. It is said that the only reason he did not win the Nobel Prize for Literature is that his colleague José Saramago did. Saramago also has a very distinctive style.

Anyway, we are now standing at the bottom of the wall of the Miguel Bombarda hospital, in the center of Lisbon.

We are standing on the road below, roughly level with the round building. This building, dating from the late 19th century, was intended for dangerous patients, who were isolated here.

Similar buildings can be found elsewhere in Europe, such as the Narrenturm in Vienna and the round prisons based on Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon. The difference here is the absence of a central observation post, which was removed at some point. Later, a museum of psychiatric art was established here.

Time to go inside, you might say. We continue along R Gomes Freire, with the wall on our right. There is always a lot of veneration of saints in a Catholic country, and we pass a statue of Maria da Graça Santos.

Then we turn right onto R Cruz da Carreira, walk slowly uphill and finally arrive at the entrance to the hospital.

Founded in 1848, this hospital remained in operation for more than 300 patients until 2012. It is now closed, but there seems to be a heated debate about what to do with the huge site in the middle of Lisbon. A number of buildings have recognized historical value, such as the round building

I have been here several times now. The first time, I stood in front of a closed gate. The second, third, and fourth times, I had a Portuguese acquaintance call the construction company’s phone number in advance. Each time, I was allowed in, and each time, there was no one there to open the gate at the agreed time, or a security guard who knew nothing about it. None of those times was there any activity on the grounds.

Very disappointing. What could have happened to the museum? We don’t know. The museum is announced on Facebook, in a post from 2019, but underneath it is a comment from someone who I think also stood in front of the gate: “Does not exist, the guard just unceremoniously ejected me from the campus. Do not waste your time getting here.”

A little frustrated, we walk away from the entrance, down R. Dr Almeida Amaral. At the bottom of the road is a small park, the Maria de Lourdes Pintasilgo Park, named after another saint, by the way. There is a vegetarian café where you can rest. If you want to continue walking, head to the nearby Campo dos Mártires da Pátria. Walk through the park and end up at the statue of Dr. Sousa Martins, the doctor from episode 1 of this series about Lisbon.

Here you will find a pdf of this episode

August 2d, 2025

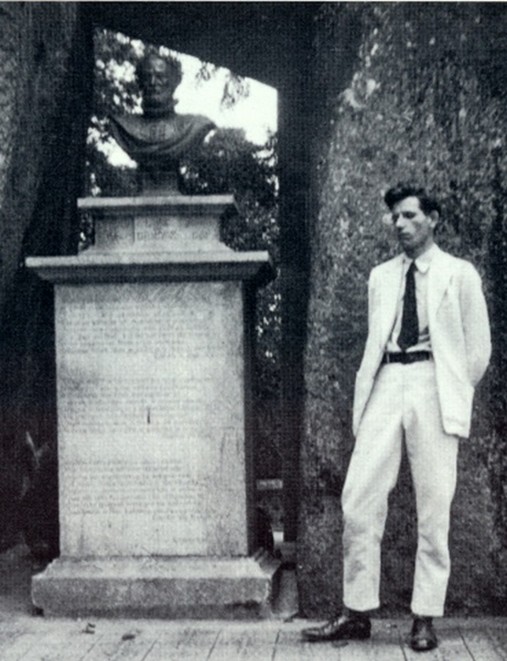

On the spot: Lisbon – Jan Slauerhoff

Where: Praça do Comércio

Cost: free

Warning for the non-Dutch reader: As you know, this is originally a Dutch side, so now and then you will stumble upon some very Dutch content. This episode of on the spot is about a in the Netherlands famous poet. This may give some problems with the translation of his poems, but we hope you still enjoy it.

There are a few places in Europe with a large square directly on the water. In the past, this was the place where people arrived to be impressed. The square in Venice is world famous, those in Trieste and Lisbon less so. The Praça do Comércio in Lisbon is not really on the sea, although the Tagus River does look like a sea at this point.

The square was built after the great earthquake that struck Lisbon in 1755. The entire lower town of Lisbon was wiped out, partly by the tsunami that followed the earthquake and then a fire. More than a third of the population died. This event caused horror throughout Europe and feelings of resistance against this blind and destructive force of nature, and thus became one of the seeds of the Enlightenment.

Marquis de Pombal took on the task of rebuilding the city, which is why Lisbon now consists of narrow, winding streets in the upper part of the city and straight lines in the lower part. The people were eternally grateful to the marquis and honored him with a statue from which he could see what he had accomplished.

Diagonally to the right of the statue, you can see the gate of the Praça de Comércio against the Tagus River. This new square, built by the Marquis of Pombal, once housed many government buildings, but now it is mainly home to restaurants. Jan Slauerhoff sat here in 1928 to enjoy a rare moment in his life. For those who don’t know, Jan Slauerhoff was a Dutch ship’s doctor and an important poet in the first half of the 20th century. He lived from 1898 to 1936. He did not live to an old age, as he was struck down by tuberculosis early in his life. He reported the following from Lisbon:

‘Praca do Commercio. Wide, spacious; an equestrian statue in front of the distant palace and below it, like a tunnel, a twentieth-century street with a tramway. Cigarettes, coffee, sitting at the balustrade, looking out over the square; in an hour, all the misery, all the stifling nights in the narrow cage, from which the sleeping body is sometimes thrown, are forgotten, by the sun, the clear sky. The lotteryseller does not nag, but points out that I have my hat on backwards. Well, Dagobert did it with his pants and hoped for immortality. (Le bon roi Dagobert/ A mis sa culotte a l’envers.) I do not hope for that from my hat. But I feel so blessed at this hour. That is enough, after a long sea voyage.

This is how the square also appeared in a poem.

After long days ravaged by the storm

And sometimes having been thrown out of my cabin,

Still bewildered by the life of gentle Lisbon,

I find myself sitting on the sunny square.

Leaning in the corner of a balustrade,

I see, as if through a window

The battered ship lying small at the quay,

The yellow stream, the colorful shore.

Below, carts rattle, cranes groan,

Here it is quiet, while only guitars

Play an old fado slowly and sadly,

And it seems as if caravels are sailing up the Tagus again.

Slauerhoff liked Lisbon. First of all, his hero, the Portuguese poet Luis de Camões, came from here. Slauerhoff was a great admirer of him and had also visited Camões’ famous cave in Macau.

Camões’ life fascinated him so much that he wrote a novel about it: Het verboden rijk (The Forbidden Empire), which was published in Dutch in 1931. A sequel appeared in 1933: Het leven op aarde (Life on Earth).

Slauerhoff first visited Lisbon in 1928, on one of his voyages with the Gelria, the ship on which he was a ship’s doctor.

‘In the afternoon I walk through the prados

And in the evening I hear the fados

Accusing deep into the night:

‘A vida e immenso tristura’

Life is immensely sad, which was the other reason Slauerhoff felt at home in Lisbon. Sadness was his attitude towards life. This sadness is expressed in Portugal in the word Saudade, which is not so easy to understand. It expresses nostalgia for the future and the past at the same time, an ambivalent feeling that gives Portuguese life a typical and difficult to explain character. And saudade is very much present in Portugal’s song of life: fado.

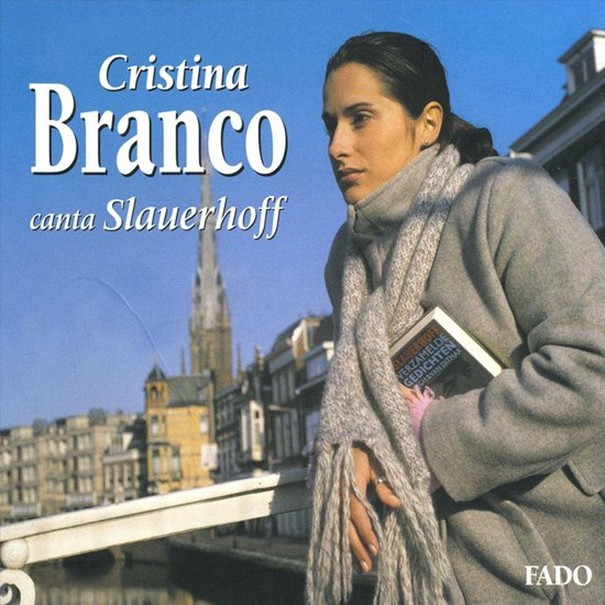

Slauerhoff wrote several poems about fado and saudade, which are of course incomprehensible to a non-Dutch reader. But the now world-famous Portuguese singer Christina Branco discovered them, had them translated, and made a fado album with the translated lyrics: Canta Slauerhoff. What would Slauerhoff have thought of that?

Here is one of these poems, with a link to Christina Branco’s performance

Fado

Am I slow because I am sad

Find everything futile and mean;

On earth I know no greater need

Than some shade under a parasol?

Or am I sad because I am slow

Never venturing out into the wide world,

Knowing only Lisbon by the Tagus

And even there existing for no one

Preferring to wander aimlessly in dark alleys

Of the poor Mourarria?

There I meet many like myself

Who live without love, lust, or hope.

Fado is the blues of Portugal, that much is clear. There is a Fado Museum in Lisbon, at Largo do Chafariz de Dentro 1, in the Alfama district. There is also a lot of attention for the grande dame of fado, Amalia Rodrigues. Well worth a visit, admission is 5 euros.

You can also listen to live fado music in various places. For an entire evening of food and music, I can heartily recommend:

Fado ao Carmo

Rua da Condessa number 52, 1200-122 Lisbon.

There is no stage; the musicians stand and sit close to you, and sometimes guests also participate (who are, of course, talented). Be sure to reserve well in advance, as it is always full in this relatively small space. 50 euros all-inclusive (the last time I was there).

Check it out on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nzmVLZ4AJNE

But for now, we’re still sitting with Jan Slauerhoff at Praça do Comercio, musing about Lisbon, that beautiful city on the Tagus River.

Lisboa

A city of gray-white buildings

And half-finished houses,

Of ruins that crumble without a trace

And columns that visibly decay.

And everywhere the rubble

Of the earthquake is still visible.

Why would anyone clear it away?

Beneath the earth, danger still lurks.

Palaces are crookedly cut off,

Others are missing a chunk of wall.

Lisbon exists in the past,

But it knows no peace, only expense.

Was it ever given to a city

To live on as a spirit,

Strange now and faithful to the past

After a rain of ashes on a feast day?

Here is a pdf of this entry

Earlier entries

July 19th, 2025

Lisbon: Fernando Pessoa (2)

Location: various locations

Duration: If you follow parts 1 and 2, the day will be almost full.

Here you can download the pdf

- Pessoa’s grave, initially

Location: Cemitério dos Prazeres

Address: Praça São João Bosco 568, 1350-297 Lisbon.

How to get there: Tram 28E, final stop (the famous yellow tram)

Opening hours: 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. (October to April) and until 6:00 p.m. in May to September

Cost: free

After his death, Pessoa was buried at the Cemitério dos Prazeres alongside his family. It is a beautiful cemetery, but it is located close to the airport, so planes fly low overhead constantly.

Upon entering, you will notice the many cats, who apparently have a good life here.

If you walk all the way to the end of the cemetery, you will look out over a valley and, on the left, the large suspension bridge over the Tagus River, the 25 April Bridge.

A Catholic cemetery with many small houses and mausoleums. This creates entire streets of the dead.

The windows are striking, allowing you to look inside.

Next to the church is a room where dissections were performed and, to my surprise, the name of Dr. Sousa Martins, the holy doctor of Lisbon, appears again as one of the users. (see On the spot Lisbon 1)

José Saramago, the Portuguese winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, has the main character in his novel The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis, an alter ego of Pessoa, the Brazilian doctor Ricardo Reis, visit the grave of his creator in this cemetery.

Saramago describes the visit as follows:

When Ricardo Reis arrived at the cemetery, the bell in the gate rang, clanging with the sound of cracked bronze, like a rural farmhouse in the languid quiet of the siesta. A handcart moved away with swaying funeral curtains, followed by a group of dark figures, women wrapped in black shawls and men in wedding suits, carrying white chrysanthemums in their arms, while whole bouquets of these flowers adorned the bier; even flowers do not all suffer the same fate. The handcart disappeared into the back of the cemetery and Ricardo Reis made his way to the administration office, the register of the dead, to ask where the grave of Fernando António Nogueira Pessoa was, who had died on the thirtieth of the previous month and been buried on the second of the current month, laid to rest in this cemetery until the end of time, when God would awaken the poets from their temporary death. The clerk realizes that he has a cultured, distinguished person in front of him and explains everything diligently, giving him the street and the number, because this is just like a city, sir, and because he gets tangled up in his own directions, he comes out from behind the counter, steps outside and points, now very decisively, to that avenue, all the way down, at the corner turn right and then straight ahead, the grave is on the right about two-thirds of the way down the street, but watch out, because it’s a small stone, you could easily walk right past it.

(….)

Ricardo Reis walked past the grave he was looking for, there was no voice calling him, Psst, here it is, and yet there are still people who stubbornly claim that the dead talk. Woe to those dead if they didn’t have a plaque, a name in stone, a number, just like the doors of the living, just to be able to find them, it was worth learning to read. Imagine an illiterate person, one of the many we have, you should take him there and say, “Here it is.” Perhaps he would look at you suspiciously, wondering if you were trying to fool him, if through your mistake or malice he would end up praying for Montecchio when Capuletto lies there, for Mendes when it is Gonçalves.

The concession certificate, Family tomb of Dona Dionisia de Seabra Pessoa, is carved on the frontispiece, under the protruding eaves of this guardhouse where the sentry, a romantic figure, is sleeping. Below, at the level of the lower hinge of the door, another name, nothing more: Fernando Pessoa, with his date of birth and death, and the gilded curve of an urn that says, I lie here, and Ricardo Reis repeats aloud, not knowing that he has heard it, He lies here, at that moment it starts to rain again. He has come from so far away, from Rio de Janeiro, has sailed many days and nights across the waves of the sea, that journey now seems so close and so far away, and what is he doing here now, at dinner time, in this street, all alone with his umbrella raised between houses of the dead, in the distance the false sound of the bell can be heard, he had expected that when he arrived here and touched that iron gate, he would feel a shock deep in his soul, a tearing, an inner earthquake, large cities collapsing in silence because we are not there, with sagging portals and white towers, and in the end it is only a slight burning sensation in his eyes, so fleeting that he did not even have time to think about it and be moved by the thought.

This fantastic novel in honor of Pessoa shows how deserving Saramago was of the Nobel Prize. Ricardo Reis, Pessoa’s creation, who still sees him occasionally, but increasingly vaguely, is himself doomed now that his creator is no longer there. It is also a novel in which Lisbon plays an important role, at a time when the Second World War is about to break out. The Portuguese dictatorship is dissected in an inimitable way. A beautiful novel.

We will encounter Saramago again in another part of Lisbon.

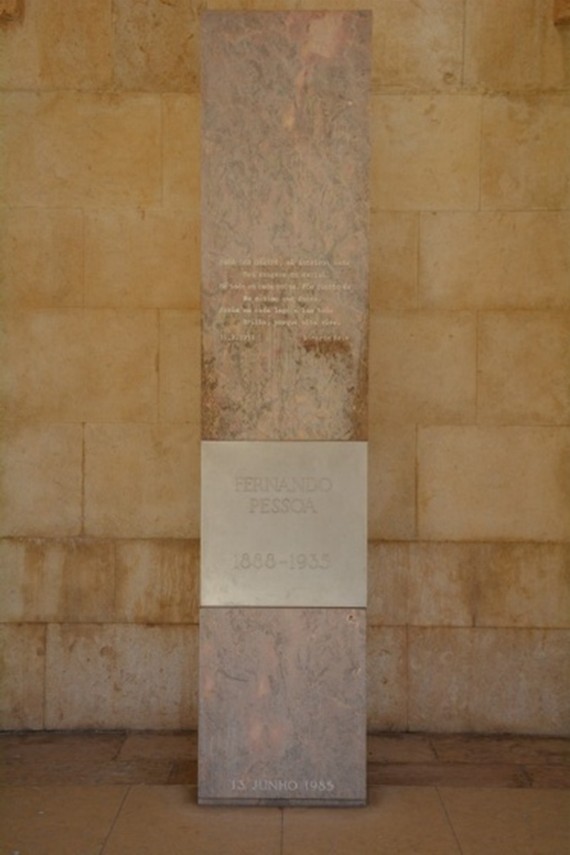

What is a problem in our time is that Pessoa is no longer here. The family tomb where he once lay is still there, but like the famous Amalia Rodrigues, the fado singer, the famous writer has been reburied in Belém, which is also the last stop on our Pessoa journey.

After a stroll through the cemetery, we return to the entrance. Here, by the way, there are toilets if nature calls. One last tip is that Campo Ourique, as the start/end point of the tram, is the perfect place to grab a seat by the open window on a yellow tram and enjoy the entire ride to Praça Martim Moniz, right through Alfama and its steep and winding streets. The ride takes at least 45 minutes.

- Pessoa’s tomb, now

Location: Mosteiro dos Jeronimos

Address: Empire Square · 1400-206 Lisbon

How to get there: tram 15E

Open: Tuesday to Sunday 9:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. (last admission at 5:00 p.m.)

Cost: €18. Online booking recommended

From Praça Martim Moniz, it is only a short walk to Praça Figueira. This is where tram 15E starts. Unfortunately, it is not usually a yellow tram, but a modern tram heading towards Belem. The tram follows the banks of the Tagus River. If you are not in a hurry, you can get off at the Cais Rocha stop to visit the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga. This museum has a magnificent painting by Hieronymus Bosch.

The Temptation of Saint Anthony. There is a somewhat paler copy in Brussels. Definitely worth a visit, but you can also save this for the return trip.

Return to the tram stop. Get off at the final stop in Belem. There are a number of interesting things to see in Belem: a museum of modern art, definitely worth a visit, a botanical garden, a bakery, the only place, according to locals, where you can get authentic pastel de nata, a tower, formerly the departure point of the great Portuguese maritime company, a monument commemorating this

and the building we want to visit, the Mosteiro dos Jeronimos. The few times I’ve been there, there were long queues. It’s a good idea to buy tickets in advance.

Once inside, you are overwhelmed by the rich architecture. The monastery dates from the 16th century, the era of the great discoveries: along the Cape of Good Hope to India (Vasco da Gama), to America (Columbus), Portugal, a small country, flourished and was present all over the world.

And Fernando is buried in that monastery. You could almost say that this monastery is the Pantheon of Portugal, were it not for the limited number of famous people buried there. Moreover, Luis de Camões is only symbolically buried here.

I would have expected that for such a versatile person as Pessoa, who had 81 heteronyms, something less boring, something more modern, could have been thought up. Both in terms of how it looks and in terms of the surroundings. Unlike at Cemitério dos Prazeres, there is no one around to chat with.

I don’t envy Fernando.

July 5th, 2025

Lisbon: Fernando Pessoa (1)

Location: various locations

Duration: If you follow part 1 and part 2, your day will be almost full.

- Café A Brasileira

Address: Graça Plaza

How to get there: Baixa-Chiado metro station, exit Baixa

Close to the square where the most famous Portuguese poet, Luis de Camões, has a statue, Praça Luis Camões, next to the entrance to the metro, is the terrace of Café A Brasileira, a café that opened in 1905. Fernando Pessoa is sitting at a table on the terrace. He is being photographed incessantly by someone who sits down on the chair next to him, but he remains cool.

He sits there like his colleague and contemporary Hemingway in Havana at the bar in El Floridita. Relaxed, with a drink. Because Hemingway and Pessoa also had that in common: their great love of alcohol.

But otherwise, these contemporaries are as different as night and day, leaving it up to you to decide who is day and who is night. A small example is Hemingway’s friendship with a dictator (see the photo in the picture) and Pessoa’s dislike of Salazar, the Portuguese dictator.

Fernando Pessoa (1888–1935) is best known for his heteronyms, the many splintered versions of the writer, each with a different body of work. The best known are Alberto Caeiro, Álvaro de Campos, Bernardo Soares, and Ricardo Reis. For Pessoa, human beings are not one-dimensional, but made up of multiple layers. Freud’s “I am not the master in my own house” is expressed in his heteronymic work. And, funnily enough, heteronyms also wrote comments about each other. His best-known work is The Book of Disquiet. That book was only published after his death, more about that later.

Only a few photos of him are known, such as this blurry one:

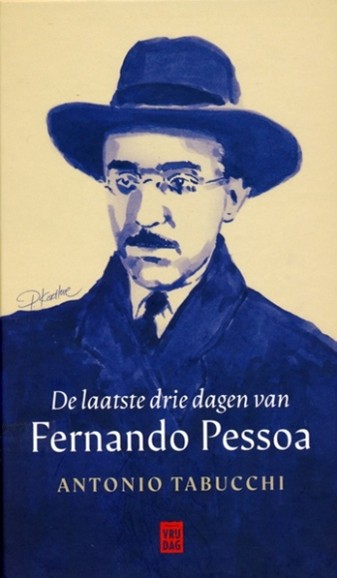

Pessoa, perhaps on his way to the terrace of Café A Brasileira. He looks comfortable sitting here on the terrace of the café. His drinking contributed to his early death, as described by Antonio Tabucchi, an Italian Pessoa expert, in The Last Three Days of Fernando Pessoa. It is a short novella, as far as I know not translated into English, in which Pessoa’s most important alter egos come to say goodbye during the last three days of his life. It is described as delirium.

“He lay in a modest room with an iron bed, a white wardrobe, and a small table. Pessoa lay down on the bed, turned on the lamp on the bedside table, rested his head on the pillow, and stroked his right side with his hand. Fortunately, the pain had eased somewhat. The nurse brought him a cup of water and a tablet and said, ‘Excuse me, but I have to give you an injection, doctor’s orders.

Pessoa asked for a dose of laudanum, a sleeping pill he was accustomed to taking when, in his capacity as Bernardo Soares, he was unable to sleep. The nurse brought him what he asked for and Pessoa drank it. “My name is Catarina,” said the nurse. “If you need anything, just call me and I’ll come right away.”

We are still on the terrace, sitting next to Pessoa. But others are eager to take our seats, so we leave Pessoa here on the terrace, because since his death he can be found in several places at once in Lisbon. So we’re on our way, but first we take a look inside what the sign on the facade says is the oldest bookshop in Lisbon, Livraria Bertrand, on R. Garrett, opened in 1732. It is even said to be the oldest bookshop in the world. It is everything a bookshop should be, but almost never is anymore. At the back is a café.

After the bookshop, we walk back a little, turn left into R. Serva Pinto and head for a square on the right with Pessoa’s birthplace, opposite the national theater. In front of that house is another statue of him.

- Pessoa’s birthplace

Address: Largo de Sao Carlos

Cost: Free

In this photo, the statue is not yet visible, but you can see the sign on the wall, just behind the lantern, indicating that Pessoa was born here. Nevertheless, the statue is well worth seeing. The way Pessoa is depicted shows that he was certainly not an open book.

If we compare Pessoa to Hemingway, Hemingway is a straightforward writer, while Pessoa writes in a labyrinthine, searching, ambiguous style. Here’s an example:

(Bernardo Soares) “I wish I were in the country, so that I could wish I were in the city. I love being in the city so much, but that way I would enjoy it twice as much.”

He is a truly remarkable writer, because he also wrote rather boring detective stories and a not very interesting travel guide to Lisbon. Originally written in English (Pessoa also translated books). The travel guide was published long after his death. But who am I to criticize someone who is considered by many to be one of the most important writers of the 20th century?

For the next step in Pessoa’s footsteps, we have to go to the house where he lived. That house is located in the Ourique district. The easiest way to get there is to take the yellow tram 28 to Campo Ourique from Praça Luis Camões. However, this tram is often very crowded, so hopefully you will be able to get on. Get off at Praça de Estrela. Perhaps take a look inside the church, and then walk a short distance.

- Pessoa’s house (now a museum)

Location: Casa Fernando Pessoa

Address: Rua Coelho da Rocha, 16-18 Campo de Ourique

How to get there: Tram: 25 and 28; Bus: 709, 713, 720, 738, and 774

Cost: 5 euros. Tickets also available online.

Opening hours: 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. Closed on Mondays.

Pessoa lived in what is still a normal street with residential houses. His house has been turned into a biographical museum.

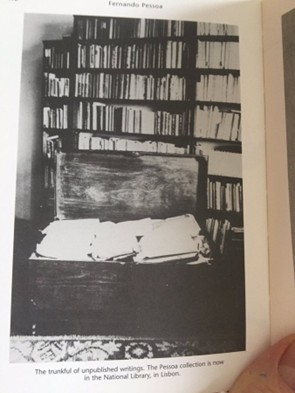

The museum naturally houses the famous mysterious box containing 27,543 manuscripts, which was found after his death.

I don’t know if the box in the museum is the real one, I suspect not, but this box plays an important role in the reception of Pessoa. It took until the 1980s before the documents were deciphered. In 1982, the first edition of The Book of Disquiet was published. This was followed by new editions in 1986, 1990, and 1998. New editions of the latest version have been published, each time with further revisions.

This accumulation of changes has to do, on the one hand, with what was found in the box, but on the other hand also with the fact that the texts were in undated envelopes. What is the correct order? And what belongs in the book and what does not? The famous Book of Disquiet has therefore been regularly revised and only became semi-definitive around 2004.

The museum is tastefully decorated and provides a nice overview of Pessoa’s life and work. On the website (which is very slow), you can also take a virtual tour of the museum, but it is much better in person.

After your visit, enjoy a nice cup of espresso at a reasonable price in the café and then move on to the next stage. You can walk back to the tram, or continue on to the Cemitério dos Prazeres. It’s only about two tram stops away, so it’s not too far.

In two weeks, we will continue our Pessoa journey.

Arko Oderwald

Here you can find a pdf.

Older entries

June 21, 2025

Lisbon: Doctor José Tomás de Sousa Martins

Location: Campo dos Mártires da Pátria, Lisbon

How to get there: bus 730.

Cost: free

There are many famous doctors in our history. Some doctors have had diseases named after them. Think of Gilles de la Tourette, Cushing, Alzheimer, Parkinson, Dupuytren. Or doctors associated with a specific medical procedure, such as the Babinski reflex, or a particular symptom, such as Cullen or Trousseau. Oh yes, there are also doctors who have become famous as writers: Chekhov, Maugham, Lobo Antunes, Williams, to name but a few.

There is a (Dutch) wikisage page with famous doctors. It is a colorful and rather random collection of doctors, many of whom fall under the above examples. What is striking is that none of these doctors became famous for their great clinical abilities, including dealing with patients in a decent manner. What we do know is that some doctors were removed from the list precisely because of their lack of the latter. For example, Friedrich Wegener (Wegener’s disease) and Hans Reiter (Reiter’s disease) were removed from the list because of their Nazi sympathies. The diseases were renamed.

But there are famous doctors who are famous for the way they treated their patients. For that, we have to go to Campo dos Mártires da Pátria in Lisbon. There stands the statue of Dr. José Tomás de Sousa Martins.

He lived from 1843 to 1897. He has a Wikipedia page in English. There we read:

He was a doctor and professor at the Medical-Surgical School of Lisbon, the predecessor of the Faculty of Medical Sciences of the NOVA University in Lisbon. He studied pharmacy and medicine and worked in Lisbon, mainly for the poor. He was particularly interested in the fight against tuberculosis. His career and his choice to work mainly for the poor people of Lisbon created an image of a saint, which is still noticeable today.

Tuberculosis, which was untreatable at the time, became his life’s work. He ensured that a sanatorium was built in north-eastern Portugal, the Sanatório Dr. Sousa Martins. Sadly, Sousa Martins himself contracted tuberculosis. It was so severe that he took his own life on August 18, 1897.

And now we are standing in front of his statue, which was erected in 1904.

The statue stands near the medical faculty where he was a professor.

He is, of course, depicted as a philanthropist, seen here on a card with a wish.

However, that is not what repeatedly catches the eye. Around the statue are stones, often made of marble, inscribed with wishes and expressions of gratitude. There are dozens, perhaps even hundreds, of wishes and expressions of gratitude from patients, one on top of the other.