Where: Praça do Comércio

Cost: free

Warning for the non-Dutch reader: As you know, this is originally a Dutch website, so now and then you will stumble upon some very Dutch content. This episode of on the spot is about a in the Netherlands famous poet. This may give some problems with the translation of his poems, but we hope you still enjoy it.

There are a few places in Europe with a large square directly on the water. In the past, this was the place where people arrived to be impressed. The square in Venice is world famous, those in Trieste and Lisbon less so. The Praça do Comércio in Lisbon is not really on the sea, although the Tagus River does look like a sea at this point.

The square was built after the great earthquake that struck Lisbon in 1755. The entire lower town of Lisbon was wiped out, partly by the tsunami that followed the earthquake and then a fire. More than a third of the population died. This event caused horror throughout Europe and feelings of resistance against this blind and destructive force of nature, and thus became one of the seeds of the Enlightenment.

Marquis de Pombal took on the task of rebuilding the city, which is why Lisbon now consists of narrow, winding streets in the upper part of the city and straight lines in the lower part. The people were eternally grateful to the marquis and honored him with a statue from which he could see what he had accomplished.

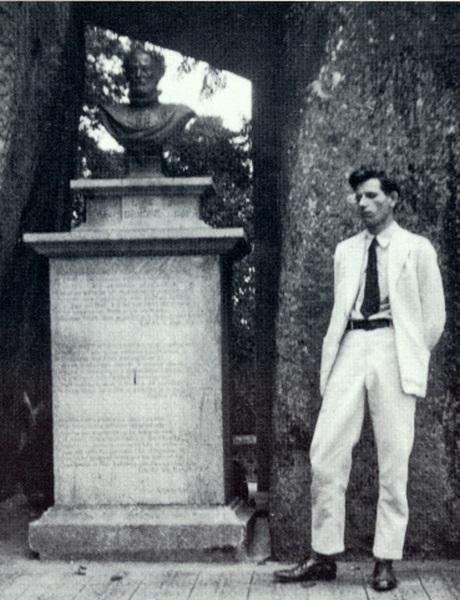

Diagonally to the right of the statue, you can see the gate of the Praça de Comércio against the Tagus River. This new square, built by the Marquis of Pombal, once housed many government buildings, but now it is mainly home to restaurants. Jan Slauerhoff sat here in 1928 to enjoy a rare moment in his life. For those who don’t know, Jan Slauerhoff was a Dutch ship’s doctor and an important poet in the first half of the 20th century. He lived from 1898 to 1936. He did not live to an old age, as he was struck down by tuberculosis early in his life. He reported the following from Lisbon:

‘Praca do Commercio. Wide, spacious; an equestrian statue in front of the distant palace and below it, like a tunnel, a twentieth-century street with a tramway. Cigarettes, coffee, sitting at the balustrade, looking out over the square; in an hour, all the misery, all the stifling nights in the narrow cage, from which the sleeping body is sometimes thrown, are forgotten, by the sun, the clear sky. The lotteryseller does not nag, but points out that I have my hat on backwards. Well, Dagobert did it with his pants and hoped for immortality. (Le bon roi Dagobert/ A mis sa culotte a l’envers.) I do not hope for that from my hat. But I feel so blessed at this hour. That is enough, after a long sea voyage.

This is how the square also appeared in a poem.

After long days ravaged by the storm

And sometimes having been thrown out of my cabin,

Still bewildered by the life of gentle Lisbon,

I find myself sitting on the sunny square.

Leaning in the corner of a balustrade,

I see, as if through a window

The battered ship lying small at the quay,

The yellow stream, the colorful shore.

Below, carts rattle, cranes groan,

Here it is quiet, while only guitars

Play an old fado slowly and sadly,

And it seems as if caravels are sailing up the Tagus again.

Slauerhoff liked Lisbon. First of all, his hero, the Portuguese poet Luis de Camões, came from here. Slauerhoff was a great admirer of him and had also visited Camões’ famous cave in Macau.

Camões’ life fascinated him so much that he wrote a novel about it: Het verboden rijk (The Forbidden Empire), which was published in Dutch in 1931. A sequel appeared in 1933: Het leven op aarde (Life on Earth).

Slauerhoff first visited Lisbon in 1928, on one of his voyages with the Gelria, the ship on which he was a ship’s doctor.

‘In the afternoon I walk through the prados

And in the evening I hear the fados

Accusing deep into the night:

‘A vida e immenso tristura’

Life is immensely sad, which was the other reason Slauerhoff felt at home in Lisbon. Sadness was his attitude towards life. This sadness is expressed in Portugal in the word Saudade, which is not so easy to understand. It expresses nostalgia for the future and the past at the same time, an ambivalent feeling that gives Portuguese life a typical and difficult to explain character. And saudade is very much present in Portugal’s song of life: fado.

Slauerhoff wrote several poems about fado and saudade, which are of course incomprehensible to a non-Dutch reader. But the now world-famous Portuguese singer Christina Branco discovered them, had them translated, and made a fado album with the translated lyrics: Canta Slauerhoff. What would Slauerhoff have thought of that?

Here is one of these poems, with a link to Christina Branco’s performance

Fado

Am I slow because I am sad

Find everything futile and mean;

On earth I know no greater need

Than some shade under a parasol?

Or am I sad because I am slow

Never venturing out into the wide world,

Knowing only Lisbon by the Tagus

And even there existing for no one

Preferring to wander aimlessly in dark alleys

Of the poor Mourarria?

There I meet many like myself

Who live without love, lust, or hope.

Fado is the blues of Portugal, that much is clear. There is a Fado Museum in Lisbon, at Largo do Chafariz de Dentro 1, in the Alfama district. There is also a lot of attention for the grande dame of fado, Amalia Rodrigues. Well worth a visit, admission is 5 euros.

You can also listen to live fado music in various places. For an entire evening of food and music, I can heartily recommend:

Fado ao Carmo

Rua da Condessa number 52, 1200-122 Lisbon.

There is no stage; the musicians stand and sit close to you, and sometimes guests also participate (who are, of course, talented). Be sure to reserve well in advance, as it is always full in this relatively small space. 50 euros all-inclusive (the last time I was there).

Check it out on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nzmVLZ4AJNE

But for now, we’re still sitting with Jan Slauerhoff at Praça do Comercio, musing about Lisbon, that beautiful city on the Tagus River.

Lisboa

A city of gray-white buildings

And half-finished houses,

Of ruins that crumble without a trace

And columns that visibly decay.

And everywhere the rubble

Of the earthquake is still visible.

Why would anyone clear it away?

Beneath the earth, danger still lurks.

Palaces are crookedly cut off,

Others are missing a chunk of wall.

Lisbon exists in the past,

But it knows no peace, only expense.

Was it ever given to a city

To live on as a spirit,

Strange now and faithful to the past

After a rain of ashes on a feast day?