Location: R. Marquês Sá da Bandeira 74, 1050-165 Lisbon

Cost: free

How to get there: Metro Azul (blue line) station Praça de Espanha or São Sebastião.

Warning for the non-Dutch reader: As you know, this is originally a Dutch website, so now and then you will stumble upon some very Dutch, or, in this case, Flemish content. This episode of on the spot is about a famous Flemish poet. This may give some problems with the translation of his poems, but we hope you still enjoy it.

R. Marquês Sá da Bandeira is not exactly an appealing street in Lisbon. For a tourist, there seems to be nothing to see here. Hidden from view in the photo, to the left of the road is a long wall that forms the boundary with the Jardim da Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, the beautiful garden of the Gulbenkian museum, so you might walk down this street to visit the garden or the museum.

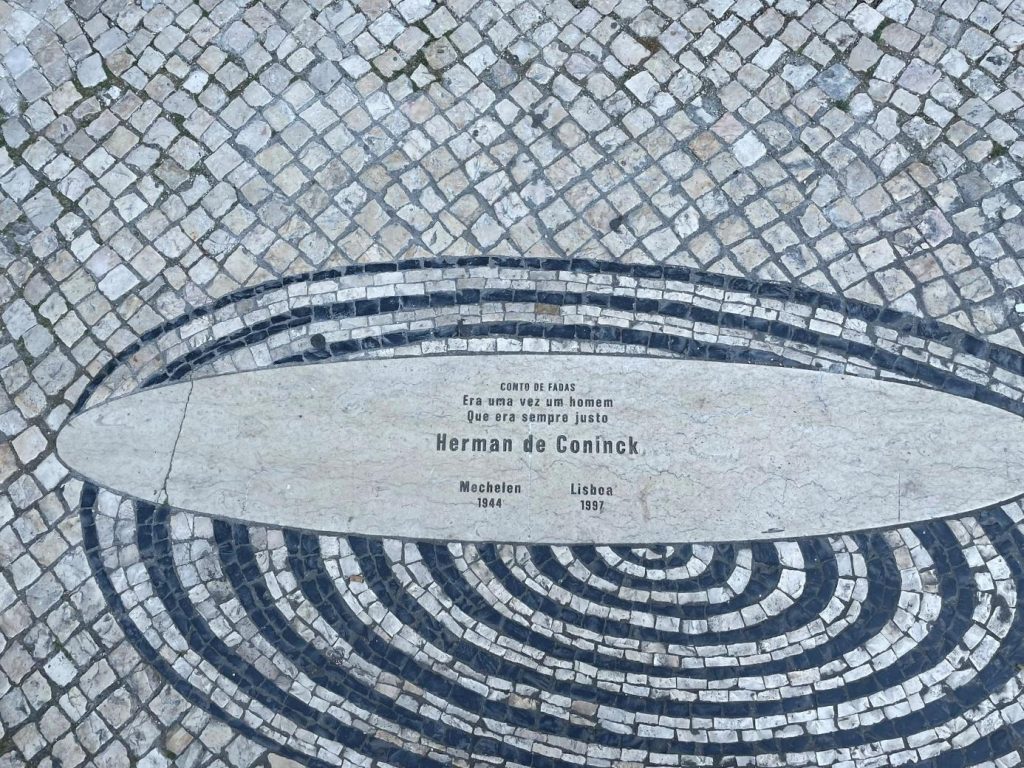

What may catch your eye in the photo is the small table with chairs to the right of the green extension of the restaurant. They are standing right on top of a memorial stone. And it is this memorial stone that will prompt some people to walk down this street.

On May 22, 1997, Herman de Coninck (Mechelen, 1944) died here on the sidewalk of R. Marquês Sá da Bandeira in Lisbon of a massive heart attack. He was only 53 years old and on his way to a literary conference. Under the auspices of the Dutch Foundation for Literature, an event was held in Lisbon from Wednesday 21 to Sunday 25 May to promote ‘Literature Contemporanea da Flandres e dos Paises Baixos’

Other Dutch writers, such as Hugo Claus, Anna Enquist, and Connie Palmen, were present when De Coninck died here, on the sidewalk.

From left to right: Tessa de Loo, Magda van den Akker, Herman de Coninck, Gerrit Kouwenaar, Margriet de Moor, Adriaan van Dis, Anna Enquist, Connie Palmen, Hugo Claus, Mirjan van Hee, behind her Gerrit Komrij.

Rutger Kopland, a good friend and Dutch poet (and psychiatrist), who was not in Lisbon at the time, wrote

“Postcard of a Greek Island.”

Herman, I wanted to write you a card,

a silly postcard with a joke

about, well, you know what,

but I heard you had already died

before I could think of a joke.

I’m still alive, our conversation isn’t over,

but I’m living these last days bent over words

that I cross out, write down again—

What were we talking about, where

had we left off, without expecting death

you don’t write poetry, we

agreed heartily,

poetry was happiness, the happiness of finding a few words

that wanted to belong together for a short instant

and before death came to take us away,

a joke, a carefully concealed joke

about death, crossing it out and writing it down again,

that would be poetry.

So I will never see you again.

These days I live bended, for all that,

for that shy body, that melancholy head

with which you spoke, for all that

gets buried alive,

I mean, I live bent over that card,

you know, with a sea that is far too blue,

the sky that is far too blue:

Happy days in Greece.

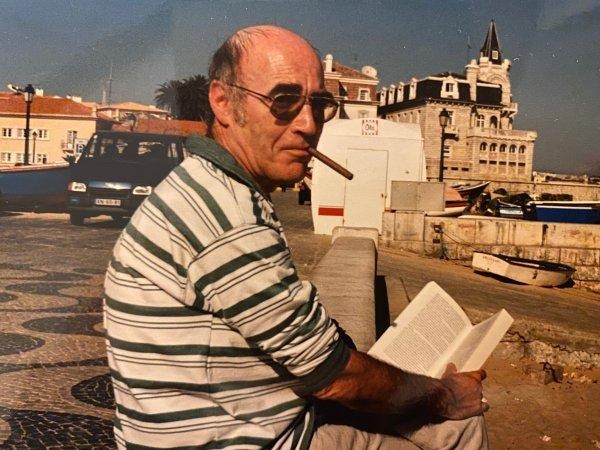

De Coninck was a much-loved Flemish poet who wrote recognizably and crystal-clear about everyday things and about major themes such as love and death. That makes his poetry timeless. In literary jargon, he belonged to the “new realists,” but he would probably have laughed at that himself, as a poet of paradoxes, reversal, negation, and disappearance.

[…]

Perhaps I learned it from my mother.

‘Son, you know,’

she said when I got married.

It took me a long time,

volumes and wives

to say so little.

To unlearn the funny, then

the grumpy, and finally

come home in the few.

From love that was pliable onto the reliable

From: Fingerprints

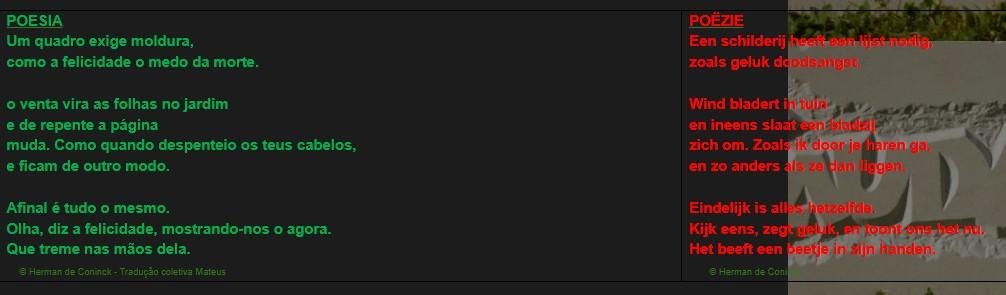

His work was also (partly) translated into Portuguese.

Poetry

A painting needs a frame

like happiness needs fear of death

Wind rustles in the garden

and suddenly a page

turns. Like when I run my fingers through your hair

and it looks so different afterwards.

Finally, everything is the same

Look, says happiness, and shows us the present.

It is trembling slightly in his hands.

In addition to his extensive oeuvre of poems, after his death, Onder literatoren (Among Writers) was published, a collection of his interviews with other writers, such as Paul de Wispelaere, Rutger Kopland, Gerard Reve, and many others. These interviews were from his time as a journalist for the Flemish magazine Humo. He would later leave Humo and found the Vlaams Wereldtijdschrift (Flemish World Magazine).

A brick-thick book of letters was also published, entitled Een aangename postumiteit (A pleasant posthumity), which reads somewhat like a biography of the years 1965-1997. The following fax to his wife is also included in that book

To Kristien Hemmerechts

Wednesday night, half past one May 22, 1997

Poes,

It’s nice here and the people are nice—but I miss you. I don’t have anyone here to say “remember…” to.

Tonight we had a nice dinner in a new neighborhood, a kind of Lisbon South, on the Tagus River, under a gigantic (xxx) Christ statue across the river. An old harbor warehouse converted into a restaurant. Afterwards we had a drink in what seemed like a terribly dirty neighborhood, in a kind of ground-floor loft: beautiful

Tomorrow morning I have a short interview in English about my poetry for the newspaper. I’m curious to see how it turns out. On Sunday evening, Veerle Claus might be able to pick us up from Zaventem.

Sweetheart, I love you and I miss you. Kisses.

Herman

This is a fax written on Wednesday night, May 21/22, and sent from Lisbon at 10:06 a.m. (local time) on Thursday, May 22, shortly before his death.

The giant Christ statue Herman refers to here is not in Lisbon, but in Almada. Dictators cannot think big enough, and this statue, commissioned by the dictator Salazar, is no exception. Including the pedestal, it is 75 meters high, and the statue itself is 28 meters high. Big enough to keep an eye on Lisbon and to be clearly seen from Lisbon. Not original, by the way; the original is in Rio de Janeiro.

It is an interesting image, though, the 25 April bridge, commemorating the revolution that overthrew the dictatorship, in one image with Salazar’s legacy.

Back to Herman de Coninck. In 2017, a real biography was published, ‘Toen met een lijst van nu errond’ (Then with a list of today around it). However, the most poignant book about Herman de Coninck is and remains ‘Taal zonder mij’ (Language without me), written by his wife Kristien Hemmerechts, in which she searches for and analyzes the autobiographical traces in his poems.

So if you do visit the museum and the garden, take a moment to pause in front of this memorial tile and let the treasure of language that ended here sink in.

Aafke de Groot and Arko Oderwald

Sources:

- Hugo Brems (ed.) Herman de Coninck. De gedichten I en II. De Arbeiderspers, 1998

- Christien Hemmerechts. Taal zonder mij. Atlas, 1998

- Thomas Eyskens and Piet Pyriens. Onder literatoren. De Arbeiderspers, 2022

- Annick Schreuder (ed.) Een aangename postumiteit. De Arbeiderspers, 2004

- Thomas Eyskens. Toen met een lijst van nu errond. De Arbeiderspers, October 2017

- Rutger Kopland. Kaart van een Grieks eiland. From: Tot het ons loslaat, van Oorschot, 1997.