On Location – Arles – Vincent van Gogh (1)

How to get there: Arles has a train station and parking garages. Except for the Van Gogh bridge, everything is within walking distance.

Cost: none

Writing about Arles and Vincent van Gogh is actually a bit like closing the barn door after the horse has bolted. There is already a description of the places he stayed there in the form of a walking tour. All you have to do is follow these stones.

This walking tour can be found at https://vangoghroute.nl/route/arles/. Those who follow the walking tour will pass all the important Vincent van Gogh locations. This article selects five of these locations.

Van Gogh stayed in Arles from February 1888 to May 1889. He came from Paris and was very impressed by the south. However, when he arrived, there was snow, as he reported to his brother Theo on February 21, 1888.

Now I can tell you that to begin with, there is at least 60 centimeters of snow everywhere and it is still snowing.

So there are not many colors yet, but it all looks very Japanese, a phrase that often recurs in his letters and with which he refers to the colors of Japanese printmaking.

Since I promised to write to you, I would like to start by saying that, because of the clarity of the atmosphere and the cheerful color effects, the region seems to me to be as beautiful as Japan. The water forms beautiful emerald and deep blue spots in the landscape, as you see in Japanese prints. Pale orange sunsets give the ground a blue appearance; brilliant yellow suns.

He writes to Émile Bernard on March 18. And on March 30, he writes to his sister Willemien:

You understand that the nature of the south cannot be painted accurately with the palette of, for example, Mauve, which belongs in the north and is and remains a master of gray. But today’s palette is absolutely colorful—sky blue, pink, orange, vermilion, bright yellow, bright green, bright wine red, violet.

But with all these colors, one comes to a new sense of calm and harmony.

He wrote to Willemien in Dutch, the other letters are mostly in French.

And that applies not only to the nature that drew him out every day, but also to the people, as he writes to Theo on May 4:

I believe there is really something to be done here for portraiture. Even though the people here are grossly ignorant about painting, in general they are much more artistic than in the North when it comes to their own appearance and their own lives. I have seen figures here that are certainly as beautiful as those of Goya and Velázquez. They know how to add a touch of pink to a black costume, or to make a white, yellow, pink, or even green and pink garment, or blue and yellow, which, from an artistic point of view, cannot be improved upon. Seurat would find male figures here who, despite their modern costumes, are very picturesque.

In a long letter to Willemien on June 20, he writes:

The color here is actually very nice; when the green is fresh, it is a rich green that we rarely see in the north, calm. When it burns and pollinates, it does not become ugly, but then a landscape takes on shades of gold of all kinds of colors, green gold, yellow gold, rose gold, ditto bronze, copper, in short, from lemon yellow to the dull yellow color of, for example, a pile of threshed grain. That with the blue – from the deepest bleu de roi in the water to that of forget-me-nots. Cobalt especially, bright clear blue – green-blue and violet-blue.

Of course, this brings out the orange—a face burned by the sun turns orange; furthermore, because of the abundance of yellow, the violet immediately stands out—a reed fence or gray thatched roof or a plowed field appears much more violet than it does at home. Furthermore, as you may already suspect, the people here are often beautiful.

He made about 190 paintings in Arles during the 15 months he was here. Three of them were destroyed in World War II. The whereabouts of two paintings are unknown, and one painting was stolen in 1944. He painted a large number of subjects several times.

The first place in Arles is where one of his most famous paintings was created: The Starry Night. We are on the banks of the Rhône.

Starry Night on the Rhône. Oil on canvas. 72.5 x 92.0 cm. Arles: September, 1888.

Paris: Musee d’Orsay

This painting should not be confused with the other Starry Night that he later painted in Saint-Rémy. Some see that painting as a reflection of his madness, but that seems to be reading too much into it. This painting is much more realistic and shows the banks of the Rhône, which are remarkably narrow here because the little Rhône has just split off. And there is something else that stands out. The painting faces south, but the Big Dipper, clearly visible, is always in the north.

Stars had recently caught his attention when he was at the seaside, he writes to Theo on June 3.

One night I walked along the deserted beach by the sea. It was not cheerful, but neither was it sad; it was beautiful.

The deep blue sky was flecked with clouds of a deeper blue than the primary blue, of an intense cobalt and others of a brighter blue, like the bluish white of the Milky Way. Against the blue background, the stars shone brightly, greenish, yellow, white, light pink—brighter, more sparkling, more like gemstones than ours—even more so than in Paris. Here, you can rightly speak of opals, emeralds, lapis lazuli, rubies, sapphires. The sea was a very deep ultramarine, the beach a purplish and soft red hue, it seemed to me — with bushes.

On September 14, he writes to Willemien:

I now absolutely want to paint a starry sky. I often feel that the night is even more colorful than the day, colored with violet, blue, and the most intense shades of green.

If you pay attention, you will see that some stars are lemon yellow, while others have a pink, green, or forget-me-not blue glow. And without going into further detail, it goes without saying that painting a starry sky is not simply a matter of putting white dots on blue-black.

We know that stars are much easier to see in dark places, and that must have been the case in 1888, when there was hardly any artificial light.

The city is nothing at night, everything is dark.

I believe that the abundant gas light, which is yellow and orange after all, makes the

blue stand out more, because at night the sky here seems to me, and this is very remarkable, blacker than in Paris.

He writes to Theo on October 11.

Now I was there during the day and the situation regarding artificial light has changed dramatically, so reliving what Vincent experienced is actually no longer possible, except during a power outage, but this river view of Arles still seems to have been preserved.

Arles now has about 50,000 inhabitants, compared to about 13,000 in Van Gogh’s time. Remarkably, those 50,000 are now just as many as in Roman times. Arles is a medium-sized city with a medieval-looking center. It is pleasant to walk through the winding streets. Take a look at the map and walk from the Rhône to our second location, the Place du Forum. Because that is where the famous café that Vincent painted is located.

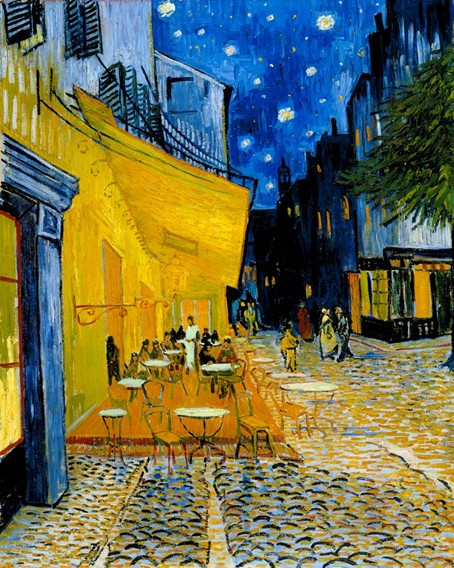

The Café Terrace. Oil on canvas. 81.0 x 65.5 cm. Arles: September, 1888. Otterlo: Kröller-Müller Museum

This is now a night painting without black. Only beautiful blue, violet, and green, and in that setting, the illuminated square takes on a color of pale sulfur yellow, greenish lemon yellow. I really enjoy painting on location at night. In the past, they used to sketch, and then during the day they would paint the picture based on the sketch. But I like to paint it immediately. Admittedly, in the dark I can mistake blue for green, blue-lilac for pink-lilac, as it is difficult to distinguish the character of the tone. But it is the only way to get rid of that conventional black night with its poor pale and whitish light, when a simple candle gives us the richest shades of yellow and orange.

He writes to Willemien on September 14.

The café has been closed since 2023 due to a dispute with the tax authorities and now looks like this:

In the 1950s, there was a furniture store here. At the beginning of the 21st century, it became a café again, painted entirely in the colors of the painting.

And then there was the Café de la Gare, Joseph Ginoux’s night café, not far from the famous yellow house where van Gogh lived. But that café, along with van Gogh’s house, was destroyed during World War II. Van Gogh painted the interior here.

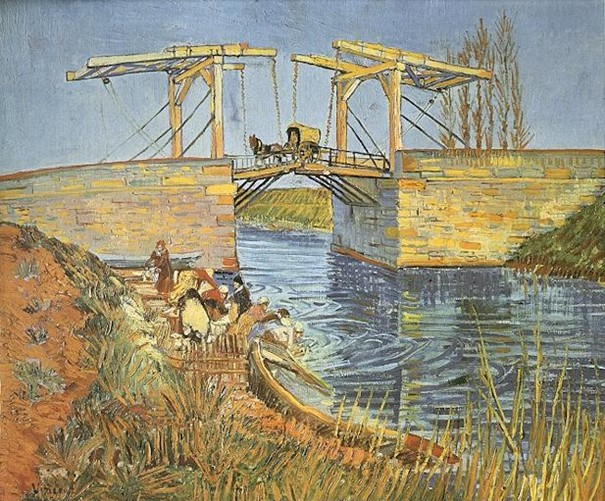

It is not always easy to be faithful to history. This becomes clear at the end of the day when we go in search of the third place, the Langlois bridge. It is walkable, but a car is preferable in this case. Van Gogh painted this bridge three times, each time slightly differently, one of which we show here.

Langlois Bridge in Arles with Women Washing. Oil on canvas. 54.0 x 65.0 cm. Arles: March, 1888. Otterlo: Kröller-Müller Museum

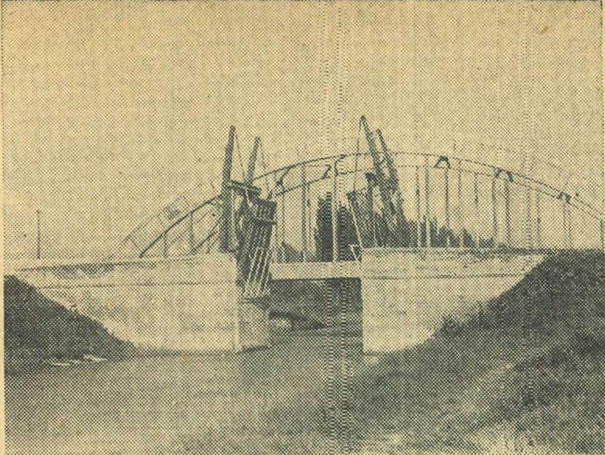

Unfortunately, the historical accuracy of this bridge is somewhat more complicated. The original bridge was located in a different place and was demolished before World War II after another bridge was built next to it. See the photo below from 1935.

The bridge we now stand in front of, now known as the Pont de Van Gogh, was a different bridge that originally stood at the very end of the canal and was rebuilt here, in a different location than the Pont de Langlois.

Even though this is closer to Arles than the original bridge, it is still not easy to get here. There are hardly any visitors. The question arises as to why something would be rebuilt to resemble a painting, in a different location, only to be allowed to fall into disrepair again.

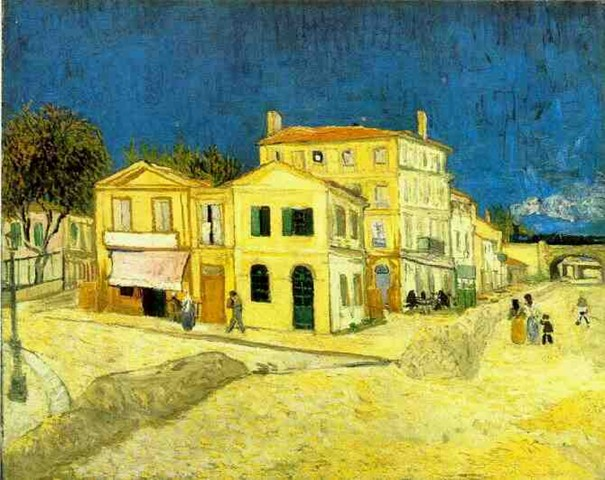

At least no one has yet come up with the idea of rebuilding the yellow house in a more easily accessible location.

Vincent’s house in Arles (The Yellow House). Oil on canvas. 72.0 x 91.5 cm. Arles: September, 1888. Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum

Of course, Arles is not yet Huis ten Bosch in Japan, where Loeki the Lion is the mascot (https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Huis_ten_Bosch_(Japan), but there are some dubious traits to be found in the attempts to market Vincent van Gogh.

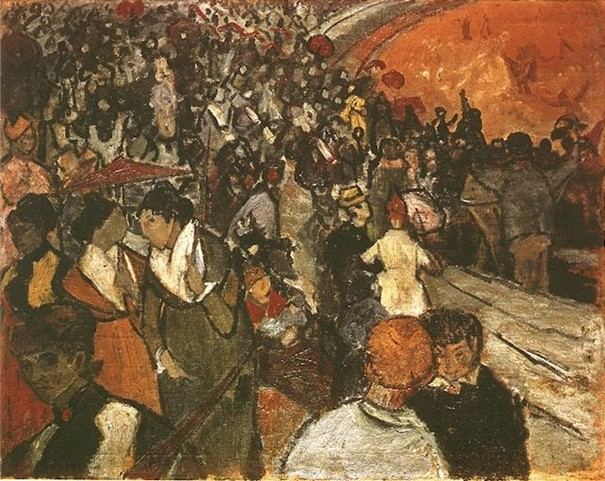

Back to Arles, because this way we forget that Arles existed long before van Gogh was there. What is now a sleepy provincial town was located at a crossroads of trade routes since Roman times. There is still a Roman amphitheater in the middle of the city, where bullfights were held in van Gogh’s time, although he did not think much of them, considering them more like games than real bullfighting.

This fourth place in Arles has also been heavily restored, of course, but at least it is still in use. Van Gogh made a painting of it, dated December 1888. What is remarkable is that he did not paint it on site, but in his studio, which was quite unusual for Van Gogh.

Gauguin had arrived, but Van Gogh had not yet gone off the rails when he painted this. There has been much speculation about Van Gogh’s illness, which is thought to have been the cause of his decline. I worked with medical experts for a while to come to a conclusion on this, but we didn’t really get any further than the personality disorder specialist finding a personality disorder plausible, the bipolar disorder specialist finding a bipolar disorder plausible, an autism specialist finding an autism spectrum disorder obvious, while a neurologist still felt some sympathy for epilepsy, the diagnosis with which Van Gogh was admitted. There was no schizophrenia specialist in the group, because then the following would also have been possible.

Well, Zeldox did not exist in 1888, and if it had, he would have had to be at least 20 kilos heavier in the Zeldox portrait.

On December 23, 1888, Van Gogh cut off his left ear, leaving only a small piece. He gave that ear to a prostitute, who probably worked in this brothel.

The Brothel. Oil on canvas. 33.0 x 41.0 cm. Arles: October, 1888. Philadelphia: The Barnes Foundation

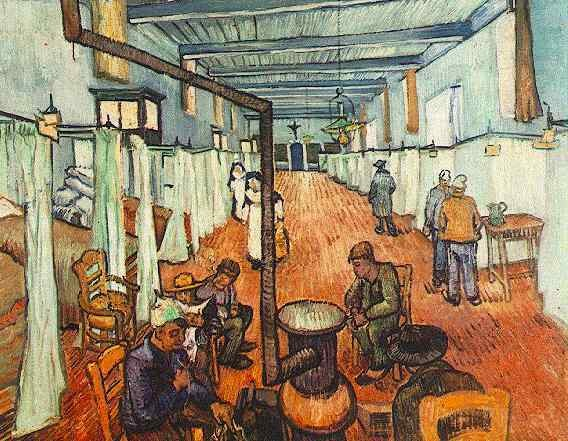

Vincent van Gogh was then admitted to the hospital in Arles, partly to have his ear treated. Two paintings were created in that hospital. Van Gogh described them to Willemien on April 28, 1889:

I am working and have just completed two paintings of the guest house. One is a hall, a very long hall with rows of beds with white curtains, where a few patients are walking around.

The walls, the ceiling with its large beams, everything is white: lilac-white or green-white. Here and there a window with a pink or light green curtain. Red tiles on the floor. In the background, a door with a crucifix above it. It is very simple.

Hall in the hospital in Arles. Oil on canvas. 74.0 x 92.0 cm. Arles: April, 1889

Winterthur: Oskar Reinhart Collection ‘Am Römerholz’

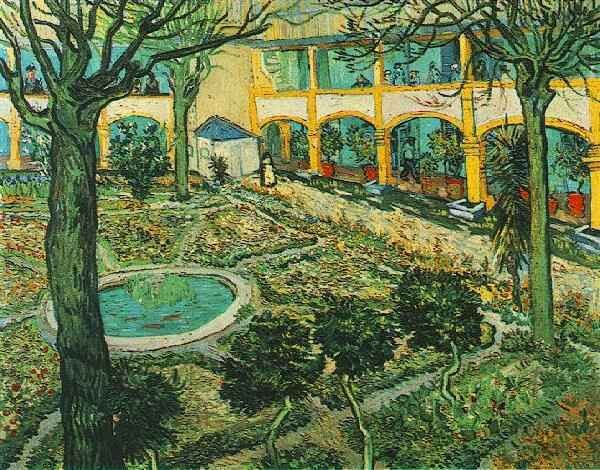

And then, as a counterpart, the courtyard. It is an arcade like those found in Arab buildings, whitewashed. In front of these arcades is an antique garden with a pond in the middle and eight flower beds with forget-me-nots, Christmas roses, anemones, ranunculus, violas, daisies, etc.

And under the gallery, orange trees and oleanders. So it is a painting completely filled with flowers and spring greenery. However, three black and gloomy tree trunks twist through it like snakes, and in the foreground are four sad, dark box trees.

Garden of the Hospital in Arles. Oil on canvas. 73.0 x 92.0 cm. Arles: April, 1889 Winterthur: Oskar Reinhart Collection ‘Am Römerholz’

This building, our fifth location, now houses the Espace van Gogh, which bears a clear resemblance to its former self. However, this courtyard garden was once a parking lot—it has been restored to the painting.

He was discharged from the hospital surprisingly quickly and wanted to return to his yellow house, but his neighbors were opposed to this and prevented it. Van Gogh himself was also not convinced that he could manage on his own, as Gaugin had left immediately after the ear incident. He returned to the hospital and eventually voluntarily admitted himself to an institution in Saint-Rémy de Provence, not far from Arles. See there.

Sources

Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten, and Nienke Bakker. Vincent van Gogh. The Art of the Word. His Most Beautiful Letters. Amsterdam: Carrera Publishers, 2014.

Paintings by van Gogh: https://vggallery.com/international/dutch/paintings/main_az.htm

Arko Oderwald and Aafke de Groot

With many thanks to Teio Meedendorp for his comments and additions.