Location: Hospital Miguel Bombarda

How to get there: Metro yellow line, Picoas station.

Cost: free

We have just stepped out of the metro at Picoas station on the yellow line. The meeting point is the kiosk. This is fitting, as the history of kiosks in Lisbon is partly intertwined with the history of the writer who is the focus of this article: António Lobo Antunes.

The Quiosques can now be found everywhere in Lisbon. There are about 70 of them scattered throughout the city. The first kiosk is said to have opened in 1869. They come in all colors and sizes, but they all have six sides and a dome that refers to the Moorish period in Lisbon, which lasted almost 700 years. Most are green, like the one in the photo above, the kiosk near the statue of Camões. You can get coffee, wine, and snacks—both savory and sweet. Around 1930, Salazar and the dictatorship came to power. Because the kiosks led to gatherings in the streets—even today there are often long lines—they were closed by order of Salazar. The dictatorship disappeared in 1974. In 2009, the Quiosques were revived, and with great success.

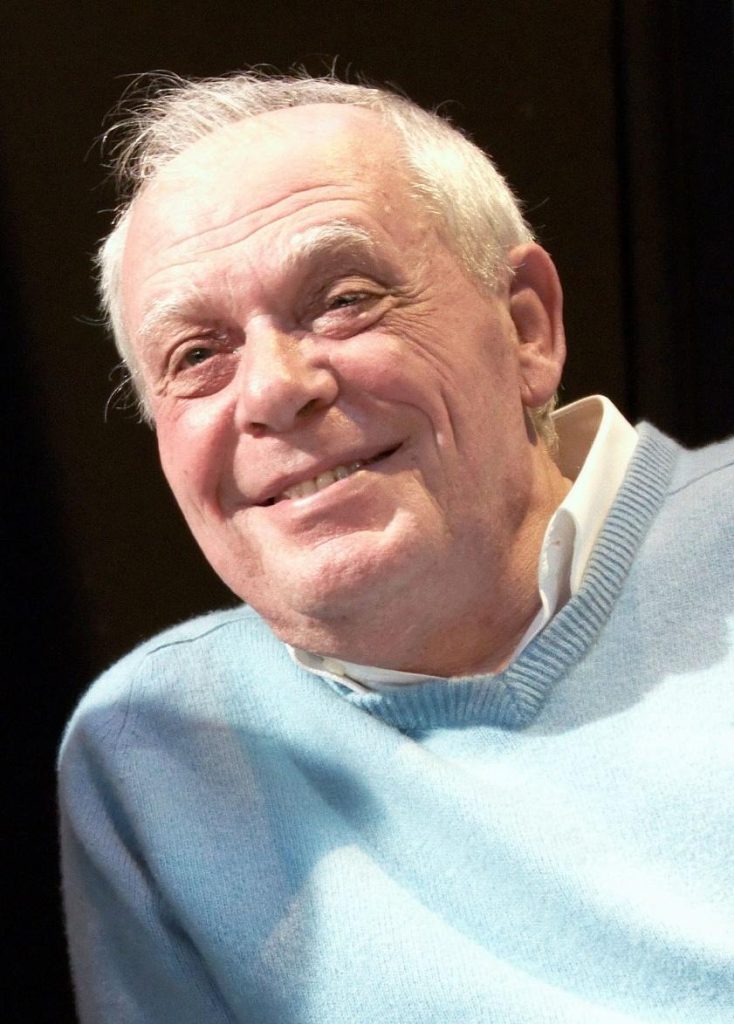

The fact that the dictatorship banned the kiosks was only a small blip in the history of the Portuguese dictatorship. Virtually no Portuguese writer was able to escape this dictatorship, not even António Lobo Antunes. Lobo Antunes is a doctor and was forced to work in Angola and Mozambique, two former colonies of Portugal. After his return to Portugal, he became a psychiatrist.

His novels often deal with the history of Portugal before and after the Carnation Revolution. Examples include Fado Alexandrino and Sermon to the Crocodiles. Later, he wrote in a more general sense about the human condition.

We are here at this kiosk

to take a look at the hospital where he was a psychiatrist and about which he wrote a novel. We are in a part of Lisbon with modern buildings, not very attractive.

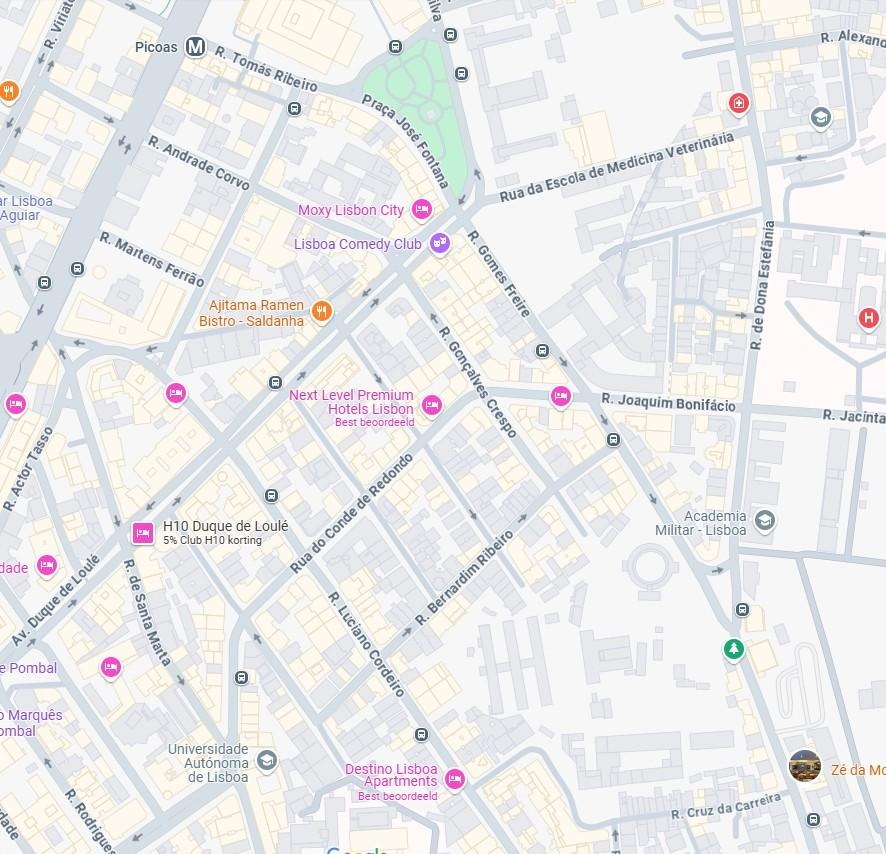

We walk into R. Tomás Ribeiro. Soon we arrive at a park on Praça José Fontana. On the other side of the park is the Liceu Camões, founded in 1910/11, which was innovative in that it had a gymnasium. Mens sana in corpore sano. We follow R Gomes Freire and after R. Bernardim Ribeiro we walk at the bottom of a hill with a wall and a high fence on top of it. Above it is the Hospital Miguel Bombarda. Running away is not only forbidden there, but also virtually impossible. It was a psychiatric institution.

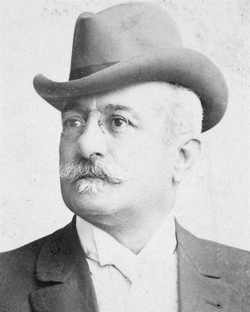

Miguel Bombarda was a psychiatrist and republican. Born in Rio de Janeiro in 1851, he was killed by a patient in 1910, two days before a revolution he had fought hard for brought down the last Portuguese king.

This psychiatric hospital is named after him. Lobo Antunes came to work here. He describes this in one of his first novels.

In Knowledge of Hell from 1980, a psychiatrist travels alone from his vacation spot in the Algarve back to Lisbon. The next day, he has to return to work at the psychiatric institution. His wife has left him and taken their two daughters with her, but that does not prevent him from occasionally talking to one of his daughters in the back seat. When he once took her to the psychiatric institution, she refused to go inside because it was too scary.

As he drives, all kinds of memories come flooding back of the horrors of his (forced) time in Angola during the war, his failed marriage, and his work as a psychiatrist. The memories merge into a massive indictment, but also into frustration about his own inability to deal with it in a constructive way.

The institution admits people who are dangerous to themselves or others, but also people who are completely harmless. Almost all of them are treated in the same way: with neuroleptics injected into their buttocks to keep them calm.

The original Portuguese title contains the word inferno, and it is a pity that this word is missing from the Dutch title, because the novel describes hell. And for Antunes, that hell is mainly in the institution and not in the war in Angola. A quote from this novel:

And it was only in 1973, when I arrived at Hospital Miguel Bombarda to begin a long journey through hell, that I realized that night had indeed left the city, that it had withdrawn from squares and cemeteries and streets and parks and crept into the corners of the wards of that hospital, just like bats, in the ceiling lamps and the dilapidated medicine cabinets, in the electroconvulsive therapy machines, in the buckets of bandages, the boxes of syringes, until the patients return silently from the dining room and crawl into their threadbare beds, after which the nurse presses the light switch and that light spreads the disgusting felt of its wings, the disgusting, sticky felt of its wings over the men, who stare at it with uncontrollable revulsion from between the sheets. The night that was leaving the city lay on the bent face of the patient who had hanged himself behind the garages, whose broken sneakers swung slightly at the height of my chin, lay in the deaths I recorded when I was on duty and pressed the ice-cold diaphragm of my stethoscope against breasts that were motionless like boats that had finally moored, lay

in the distraught features of the living who were locked up between the walls and bars of the asylum, in the dust in the courtyards in summer, in the facades of the houses around. In 1973, I had returned from the war and knew everything about the wounded, about the cries of the wounded on the road, about explosions, gunshots, mines, about bellies torn to pieces by the explosion of an ambush, I knew about the wounded and murdered babies, knew about spilled blood and homesickness, but I had been spared hell.

This quote already shows the great evocative power of Lobo Antunes’ style. That style has since developed into a highly recognizable and unique poetic way of writing prose. If you like it, and that is by no means everyone, each new book of his is a feast. Polyphony, multiple voices alternating with each other and playing with time, is characteristic of his novels. It is said that the only reason he did not win the Nobel Prize for Literature is that his colleague José Saramago did. Saramago also has a very distinctive style.

Anyway, we are now standing at the bottom of the wall of the Miguel Bombarda hospital, in the center of Lisbon.

We are standing on the road below, roughly level with the round building. This building, dating from the late 19th century, was intended for dangerous patients, who were isolated here.

Similar buildings can be found elsewhere in Europe, such as the Narrenturm in Vienna and the round prisons based on Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon. The difference here is the absence of a central observation post, which was removed at some point. Later, a museum of psychiatric art was established here.

Time to go inside, you might say. We continue along R Gomes Freire, with the wall on our right. There is always a lot of veneration of saints in a Catholic country, and we pass a statue of Maria da Graça Santos.

Then we turn right onto R Cruz da Carreira, walk slowly uphill and finally arrive at the entrance to the hospital.

Founded in 1848, this hospital remained in operation for more than 300 patients until 2012. It is now closed, but there seems to be a heated debate about what to do with the huge site in the middle of Lisbon. A number of buildings have recognized historical value, such as the round building.

I have been here several times now. The first time, I stood in front of a closed gate. The second, third, and fourth times, I had a Portuguese acquaintance call the construction company’s phone number in advance. Each time, I was allowed in, and each time, there was no one there to open the gate at the agreed time, or a security guard who knew nothing about it. None of those times was there any activity on the grounds.

Very disappointing. What could have happened to the museum? We don’t know. The museum is announced on Facebook, in a post from 2019, but underneath it is a comment from someone who I think also stood in front of the gate: “Does not exist, the guard just unceremoniously ejected me from the campus. Do not waste your time getting here.”

A little frustrated, we walk away from the entrance, down R. Dr Almeida Amaral. At the bottom of the road is a small park, the Maria de Lourdes Pintasilgo Park, named after another saint, by the way. There is a vegetarian café where you can rest. If you want to continue walking, head to the nearby Campo dos Mártires da Pátria. Walk through the park and end up at the statue of Dr. Sousa Martins, the doctor from episode 1 of this series about Lisbon.