On the spot – Lisbon – what remains

In eight episodes, we have reviewed all kinds of literary and medically relevant places in Lisbon. Although this collection can always be expanded later, in this – for now final – episode about Lisbon, we will briefly focus on a few places in Lisbon that are also worth visiting and – we will start with this – on two writers who repeatedly appear in the works of the writers already discussed: Luis de Camões and Eça de Queirós.

Here is the pdf

Writers

Luis de Camões

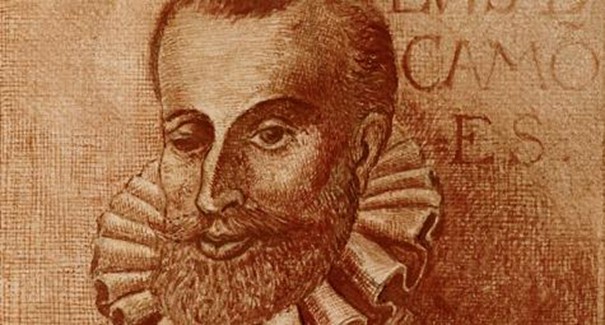

Every culture and every country has its own mythological figures. In the Netherlands we have William of Orange and Johan Cruyff, Portugal has Luis de Camões and Ronaldo. Luis de Camões lived from 1524 to 1580. He had a rather turbulent life, and since 1867 he has been depicted in the center of Lisbon as a warrior and a poet who was not always popular with those in power.

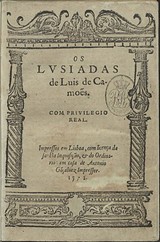

According to tradition, he died on June 10, which is now a national holiday in Portugal. People celebrate his turbulent life on that day. In 1548, he was banished from Portugal and went to Morocco, where he lost an eye. In 1553, he ended up in prison, and once released, he left for Goa, and from there he traveled on to Macao in 1555. There he wrote his masterpiece, Os Lusiadas. Every child in Portugal has read it at school. Here is a very small excerpt from Os Lusiadas.

I bid you farewell, my life! For

I already feel death living in my life.

Why, I ask, should I still strive for happiness,

If those who achieve the most lose the most?

But on this I give you my firm hand

That, even if my torment kills me,

Your memory will survive Lethe

And sail safely to the other side.

Honor without you brings tears to my eyes

Rather than rejoicing in anything else;

Better to forget them than for them to forget you.

Better that this memory cause them to suffer

Than that, by allowing your image to fade,

They be deemed unworthy of the glory of that sorrow.

Waters of the Mondego, benevolent

And gentle to my longing, where for a long time

I cherished hope, believed in deceit

And followed it, as if I were blind:

I now take my leave of you; but I am still bound

By the longing that guides me

And does not allow me to part from you:

The further away, the closer I find myself.

Even if Fate takes this prison

Of the soul to foreign lands, new songs,

To distant seas, storms and darkness,

The soul itself watches you from here

And flies on wings of swift desire

To you, O waters, to bathe in you.

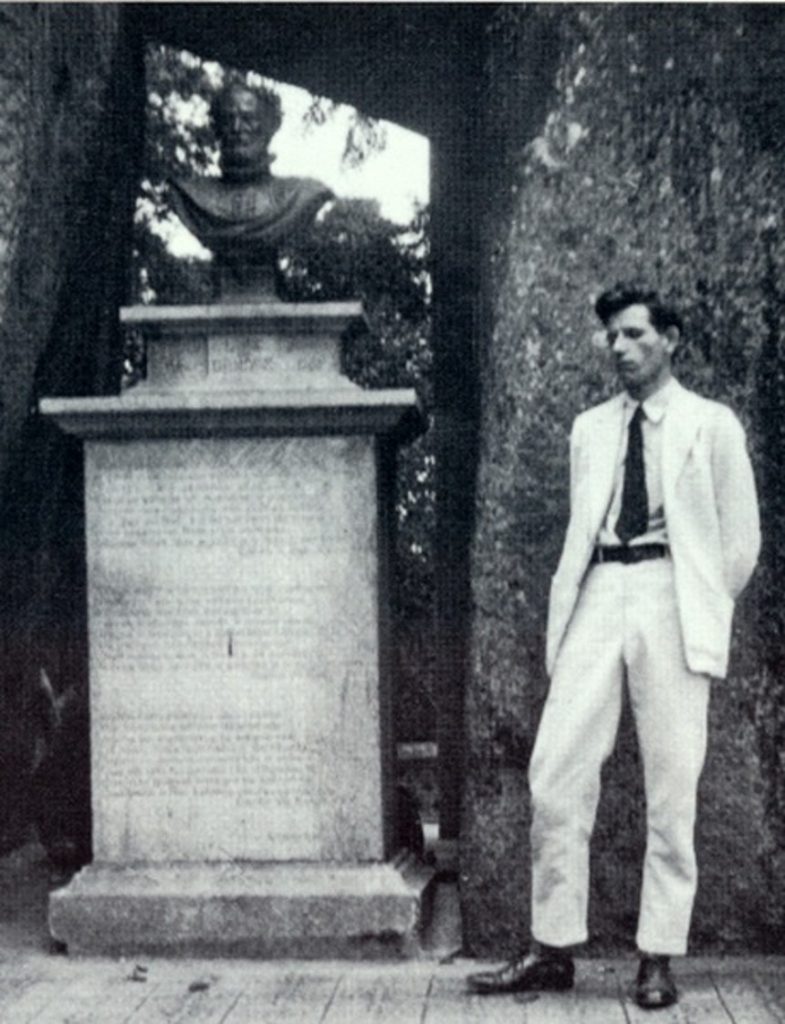

It is not difficult to see why Slauerhoff was so fascinated by Camões: the traveler and poet came close to him. No wonder he went to visit the famous cave in Macao.

Macao looks a little different now, by the way.

Slauerhoff wrote a number of poems about Camões, of which here is an example

Camões

He spent his youth in a remote castle

And served a court, spiritless, frivolous, and arrogant.

He fled, wildly yearning for a greater destiny,

Alone to the newly established States.

For his silence and uncertain shot

Despised by merchants and soldiers;

On board, in the fort, prey to the dull conspiracy

That he could not eradicate, only hate powerlessly.

Yet his dream persisted until its realization:

When he did not go to conquer strange wonderlands

With a mighty armada,

He wrought in the chilly twilight of the cave

Doomed poet, wanderer, and exile –

The heavy stanzas of the Lusiade.

(Grotto, Macao)

We owe it to the brave Luis de Camoes that Os Luciadas can still be read today. Shipwrecked off the coast, he had to swim ashore, but fortunately he kept the book above his head.

Once he arrived in Lisbon, a cold reception awaited him.

To my friends

Happiness, hoped for too long, always turns to sorrow.

When we first saw the landmark: Cintra’s hills,

Heitor was also carried to the aft deck

And slid into the sea from under the red-green cloth.

Then, right across the horizon, came the blue Tagus and

The brown hills receded, as the crow flies:

As if the fatherland opened its arms,

Wanting to carry us back to its heart.

No bonfires blazed in Lisbon.

A yellow flag flew from the old fort.

No pennants fluttered from the empty walls.

The fleet was kept at anchor, fearful of the plague.

After seven days in the city,

Unaccompanied by anyone, we went together

Like ghosts in broad daylight through strange streets,

No cheering crowds, no women waving from the windows.

At court, no one knew our names anymore.

The new states were hardly known;

The monarch, controlled by women and prelates,

Remained cold to Macao’s foundation, Goa’s fame.

I felt betrayed by seven years of work;

I had raised my Lusiade

In ship’s holds, caves, and hermitages, day and night,

Saved from fire and shipwreck like my wife.

To give it to the fatherland:

But where the enemy lies at the borders,

Where pestilence reigns, earthquakes threaten

The people are oppressed, monastery after monastery is founded,

Heretics are killed, the glory of discovery is silenced,

There is only scorn for the heroic poem.

He died in 1580 during a plague epidemic. He disappeared into a mass grave, but was later given a beautiful tomb (where he does not lie) in the Mosteiro dos Jerónimos in Belem, where we had previously visited the tomb of Fernando Pessoa.

“Here lies Camões, prince of poets of his time. He lived poor and miserable, and so he died.”

Ricardo Reis, as the character created by José Saramago, also honors Camões.

Ricardo Reis crossed the Bairro Alto and ended up back at Camões via the Rua do Norte, as if he were in a maze that kept leading him to the same place, to this half-nobleman and half-soldier, a kind of bronze d’Artagnan, crowned with a laurel wreath because he had managed to snatch the queen’s diamonds from the machinations of the cardinal at the last minute, whom he would later serve when times and politics had changed, but it would be good if our poet here, dead and therefore no longer able to serve, knew that the rulers, including cardinals, take turns or simultaneously make use of him whenever it suits their purposes. It is time to eat, the morning has been spent walking and exploring, apparently this man has nothing else to do but sleep, eat, walk, occasionally write a line of poetry, and even that with pain and difficulty, sweating over meter and rhyme, incomparable to the uninterrupted duel of our musketeer. Os Lusiadas alone has more than eight thousand verses, and yet this is also a poet, not that he boasts of that title, as can be seen in the hotel’s guest book.

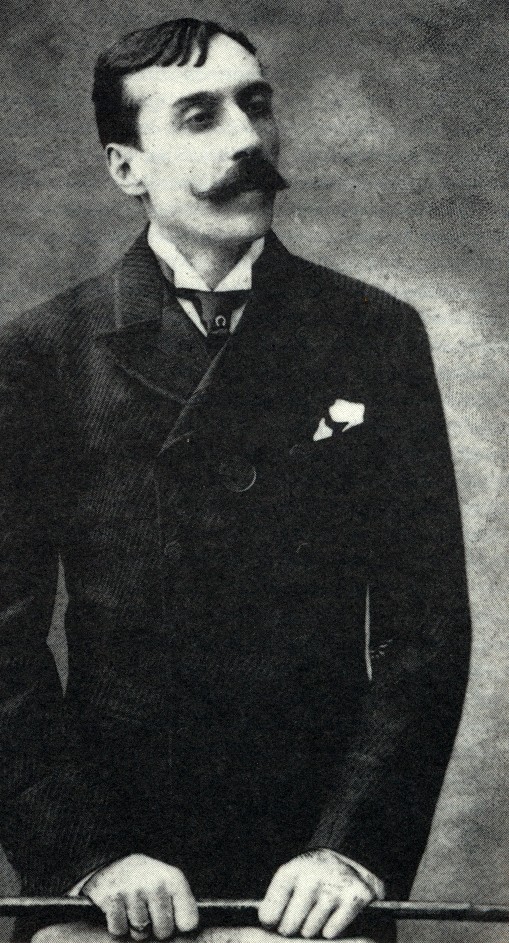

Eça de Queirós

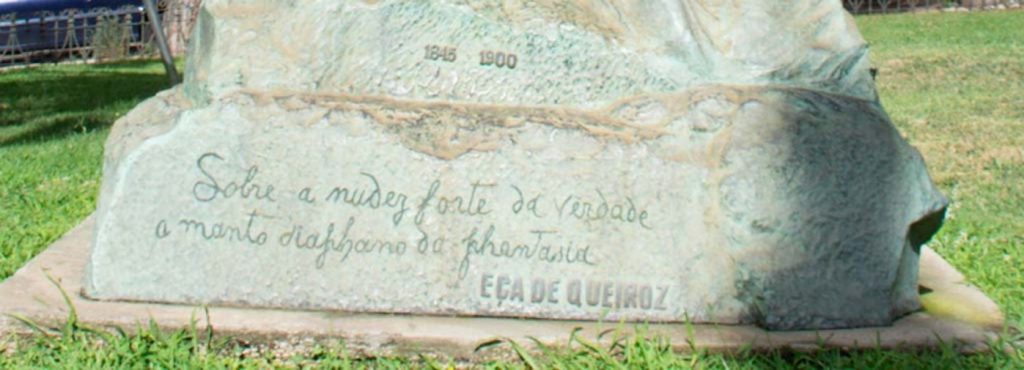

Ricardo Reis knows his classics, because he not only reflects on Camões, but also on José Maria Eça de Queriós, who lived from 1845 to 1900. He only came to live in Lisbon after completing his studies. He spent the first six years at Rossio, at no. 26. In Lisbon, he was a dandy-like intellectual who criticized the narrow-mindedness of his time. He, too, almost always moved in the vicinity of the statue of Luis de Camões, which cannot be a coincidence. The house of the main character in one of Eça’s novels was located on Largo do Quintela, and now there is a statue of the writer there.

About the raw nakedness of truth, the transparent cloak of fantasy,

is written under the statue. The naked woman must then represent the truth.

Saramago, as Ricardo Reis, also discusses the statue.

Reis pauses in front of the statue of Eça de Queirós, or Quei¬roz, out of respect for the spelling used by the bearer of the name, oh how different spellings can be, and a name is actually nothing, it is downright bewildering that these two speak the same language and one is Reis, the other Eça, probably the language chooses the writers it needs, uses them to express a small part of what it is, I wonder how we should live when the language has said everything and falls silent. The first problems are already beginning to arise, or no, they are not yet real problems but different, contradictory layers of meaning, stirred-up sediments, new crystallizations, for example, Over the solid nakedness of truth the diaphanous cloak of fantasy, the statement seems clear, clear and distinct, a child could understand it and repeat it flawlessly in a test, but that same child would understand and repeat another saying with equal conviction, Over the solid nakedness of fantasy the diaphanous cloak of truth, and this saying does give food for thought and pleasant fantasizing, naked and solid the fantasy, only diaphanous the truth, if the statements derived from their opposites became laws, what kind of world would we make of it, it would be a miracle if people didn’t go crazy every time they opened their mouths.

We walk away from the statue again. We eat a pasteis at Cister

and finally end up at Largo do Carmo, where we can admire both the cathedral, destroyed in the earthquake, and the former Hotel Bragança, which is now the headquarters of the Guardia Nacional. This is where the Carnation Revolution took place. From here, we can descend to the Rossio again. There stands the statue of Pedro IV, a statue with a remarkable history. It was a statue of Emperor Maximilian of Mexico. In 1867, it was ready for transport to Mexico, but the emperor was executed. The Portuguese government took over the statue for next to nothing, added a beard (Maximilian did not have a beard) and placed it on a very high pedestal of 27 meters. No one noticed that this was not Pedro IV, the 28th king of Portugal and the first emperor of Brazil.

Quite a bit of Eça’s work has been translated into Dutch and English as well. Some say he is the Zola of Portugal, but that is only indirectly true. It is usually not medical-literary prose, but that should not be a problem.

Places

Aqueduct and Water Museum

Aqueduct address: Calçada da Quintinha Campolide

Reservoir address: Reservatório da Mãe d’Água das Amoreiras, Rua das Amoreiras

Museum address: Rua do Alviela

The greatest contribution to our health is undoubtedly the sewerage system and clean drinking water. In the second half of the 19th century, major works were undertaken to achieve this. This was also the case in Lisbon. First, there is the enormous aqueduct, the aqueduto das Águas Livres. The need for clean drinking water was already clear in the 18th century, and in 1731 work began on this waterway, with a total length of 58 kilometers. Part of this is the aqueduct over the Alcantara valley, which is 941 meters long and 65 meters high. The aqueduct was completed in 1748. The earthquake of 1755 destroyed much of Lisbon, but the aqueduct withstood it.

The aqueduct is also open to visitors. For a few euros, you can walk across the aqueduct. It is a bit disappointing that, somewhere just over halfway, you cannot continue and have to walk back. But on the other hand, if you could continue, you would be on the other side and the way back would not be so easy. Be sure to bring an umbrella, not only if it threatens to rain, but also to protect yourself from the sun.

The water then had to be collected somewhere, so basins were built for this purpose. One of the basins can be viewed in the Reservatório da Mãe d’Água das Amoreiras. The reservoir has a capacity of 5,500 cubic meters.

The history of the water can be found in the museum, but that is on the other side of the city.

Across the Tagus

Normally, you wouldn’t immediately think of crossing the Tagus. You can do so via the 25 April Bridge, but that’s probably not possible on foot. Another option is to take the ferry from Cais do Sodre to Casilhas, which takes 10 minutes. There you can hop on a (modern) tram, but that’s not really that interesting. It’s more fun to turn right immediately after arriving and walk along the Tagus. There is a whole row of ruins of houses there, where no one seems to live (but that’s not entirely true). Behind the houses is a fairly high wall. Be careful when walking, as there are holes in the road. It seems to lead nowhere, but turn left at the end and you will see a small bay with two restaurants.

It’s definitely worth eating here, but reservations are not easy to make, as emails are not answered. But if you succeed, you’ll have a beautiful view.

If you continue walking, you will come to a tower with an elevator. If the elevator is working, you can go up. The tower is connected to the hill by a bridge. There used to be a café there, where you could enjoy an espresso while looking out over Lisbon. Perhaps it is open again now. You can walk back along the top and you will end up back at the ferry.

You can also walk around the bottom of the tower, follow the Tagus River, and you will probably arrive at the restaurant that Herman de Coninck mentioned, at the foot of the Christ statue.

Tile Museum

Lisbon is the city of tiles, the azulejos. Many houses in Lisbon are covered with tiles. These tiles have a history that can be explored in the Tile Museum.

The Tile Museum is also the last topic we will mention about Lisbon. We may return here in the future, but for now we will conclude. Next time, not a city, but a person: Vincent van Gogh.