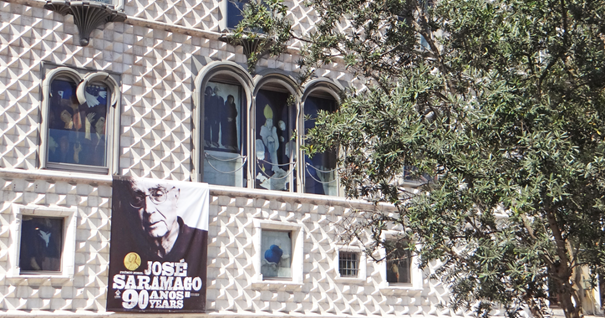

Location: R. dos Bacalhoeiros, Fundação José Saramago

Cost: 4 euros.

We are standing near the Tagus River on R. dos Bacalhoeiros, in front of an olive tree. That olive tree is not here by chance. Beneath that tree lies José Saramago, or at least his ashes. Next to the tree is the text

Mas não subiu para as estrelas s’e a terra pertencia, loosely translated as:

But he did not ascend to the stars if the earth belonged to him

The tree stands in front of the house that houses the Fundação José Saramago, a biographical museum dedicated to José Saramago. The house is a restored 16th-century building, the Casa dos Bicos. The museum provides a fascinating insight into the life of José Saramago.

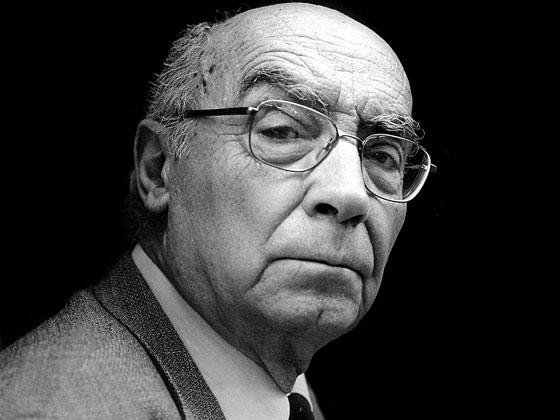

Lisbon was the city of Nobel Prize winner Saramago, although he was not born here. However, the cities in his novels are not always directly traceable to Lisbon. I think there is a reason for this, because Saramago was not on speaking terms with those in power. Born in 1922 and deceased in 2010, he experienced both the dictatorship and the post-dictatorship era. Unlike Lobo Antunes, Saramago did not come from a wealthy family, but from a family of day laborers. He worked as a mechanic and later as a journalist. His first novel was not a success, and then there was a 20-year hiatus. It was not until 1980 that he became known as a writer with a novel about the harsh life in the countryside, in which his communist sympathies clearly resonate. This novel also saw the first appearance of Saramago’s typical style. There is little white space on the page, the paragraphs are long, the dialogues are written in continuous lines, with only a comma and a capital letter indicating a change of speaker. Punctuation is unusual. This creates a compelling rhythm.

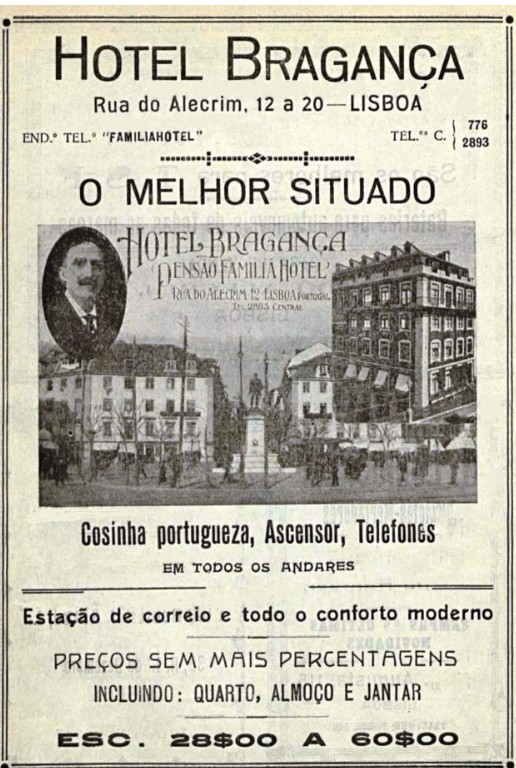

Where to, but the answer came earlier, still hesitant, uncertain, To a hotel, Which one, I don’t know, and at the same moment he said that, I don’t know, the traveler knew what he wanted, with such firm conviction that it seemed as if he had been thinking about that choice throughout the entire journey, One that is close to the river, down here, Then only the Bragança comes into consideration, on Rua do Alecrim, I don’t know if you know it, I can’t remember the hotel, but I know the street, yes, I lived in Lisbon, I’m Portuguese, Oh, you’re Portuguese, I thought you were Brazilian, the way you talk, Is it that noticeable, Well, noticeable, you can hear it, I haven’t been to Portugal for sixteen years. That’s a long time, a lot has changed in that time, and with those words the driver abruptly fell silent.

(The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis)

And finally, there is a strong magical realism in many of his novels. The latter may also provide a clear reason why his novels feature cities that resemble Lisbon, but are not Lisbon. His novels are often parables with a general message and can therefore take place anywhere.

As mentioned, Saramago and those in power did not get along. This was true not only during the dictatorship, but also after it. Although this dictatorship ended with virtually no bloodshed, the Carnation Revolution, it also ended without anyone being held accountable. The executioners of the dictatorship were not punished. No bloodshed sounds good, of course, but much of the suffering went unpunished and thus had the chance to fester beneath the surface. Saramago therefore left Lisbon and Portugal and went to live in Lanzarote (Spain).

His most famous novel is undoubtedly Blindness.

There is a sudden epidemic of acute blindness. People move through the city in rows, holding on to each other, as in Breugel’s painting.

Pieter Bruegel: The Parable of the Blind. Museo di Capodimonte, Naples.

It soon becomes clear how thin our layer of culture is in the face of a threatening infectious disease. Everyone is left to fend for themselves. The power of the story lies in the idea that something like this could happen to any of us, not just the people of Lisbon. But an epidemic is not a magical realist element, as the COVID period made clear. During our COVID period, novels that had already described such a scenario were often mentioned, with Albert Camus’ The Plague scoring highly. But Philip Roth’s Nemesis comes closer, and Blindness also comes close when it comes to the actions of the government, even though Saramago’s is much more merciless and violent.

The magical realism of Saramago’s books is sometimes truly implausible, yet convincing. In The Cave, Plato’s cave is discovered during the construction of a supermarket, and in Death with interruptions, Death stops doing his job. People in an unspecified country no longer die. Before you start cheering, remember that people who are dying still suffer, but they no longer die. If these people are taken across the border, they do die. Life insurance companies are happy because they don’t have to pay out. The church considers it a scandal, because the church exists because of the promise of an afterlife, eternal life, whether that be heaven or hell.

Saramago writes parables with a general message, which is why explicit references to Lisbon are unnecessary. That is to say, most of the time. I previously wrote about Pessoa and Saramago’s novel The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis. In that novel, the real Lisbon does play a role.

Ricardo Reis comes to Lisbon after the death of Fernando Pessoa. Reis is one of Pessoa’s heteronyms. He is a Brazilian doctor who writes poetry. Upon arrival in Lisbon, he takes up residence at the Hotel Bragança, Rua do Alecrim.

The hotel is still there, but it now has a different name. From there, Reis walks through the neighborhood, with Praça de Luis Camões as its center. Eventually, he finds work as a doctor on that square. Reis stays at the hotel for a while, but then moves to Rua de Santa Catharina, near the mirador of the same name.

A few minutes later, Ricardo Reis was standing on Alto de Santa Catarina. Two old men were sitting side by side on a bench looking at the river. They turned around when they heard footsteps, and one said to the other, “Gosh, that’s the guy who was here three weeks ago.” He didn’t need to provide any further details; the other immediately added, “The one with the young lady.” Many other men and women have passed by or stopped here in the meantime, but the old folks know exactly who they are talking about. It is a mistake to think that you lose your memory with age, that only the oldest memories remain intact and gradually resurface, like hidden tree trunks when the water recedes after a flood. There is one terrible memory in old age, that of the last days, the last image of the world, the last moment of life.

It is not far from the hotel. Via Praça de Luis Camões, we follow the yellow tram into Rua do Loretto. After a while, on our left, we see the upper station of one of Lisbon’s three cable cars. We already encountered one of the other cable cars in the first episode. The third cable car recently had a disastrous accident. Just after the cable car, turn left onto Rua Marechal Sandanha. At the end of the street is the Pharmacia museum, a museum about the history of pharmacy in Portugal. It is not a spectacular museum, but it does provide a solid overview.

Next to the museum is the Pharmacia restaurant, serving delicious Pharmacia-style food, with lots of pharmaceutical cabinets in the dining room and pharmaceutical accessories on the tables. Be sure to make a reservation in advance (and hope you get a reply).

Then take a look at the view from the Mirador Santa Catharina. This is where Ricardo Reis comes to live, and here too there is a Luis de Camões view: a statue of a mythical hero from his work: Adamastor

From here, it’s not far to Rua da Esperança, where Saramago lived at number 76. Saramago regularly ate at the Varina da Madragoa restaurant, Rua das Madres 34.

We are almost at the end of our Saramago walk. But to honor his first novel, which is set in the Alentejo, we are going to have dinner at Casa de Alentejo. From Praça Santa Catharina, we walk back up and turn right at the top, once again to Praça de Luis Camões. We walk straight ahead and at Café Brasilia, where Fernando Pessoa still sits, we enter the metro and exit at Baixa. Turn left towards Rossio and then walk past the Teatro Nacional on the right, before turning into Rua das Portas de Santo Antão. Casa de Alentejo is at number 58.

The Casa de Alentejo is not particularly striking from the outside. Anyone looking for a restaurant would probably walk right past it. But once inside, that changes. It looks like a very old Moorish building.

But that’s all fake. The building dates from the late 17th century, but was completely renovated in the early 20th century to its current state. It used to house a casino. In 1939, it became a cultural center for the Alentejo region, and it remains so to this day. It is a conference center, a restaurant, a café, and a sales point for artistic products from the region.

Above, we see the conference hall. In addition, there is excellent food in an old dining room with many tiles on the wall.

Be sure to make a reservation in advance, as it is a popular restaurant.

Arko Oderwald