This edition features a powerful Georgian film about a gynecologist in trouble and a French classic from the early 1960s about a young woman who wanders through Paris while waiting for the potentially serious results of her medical examination.

Here you will find the PDF of this edition.

Film

April, now in theaters

Gynecologist between law and personal morality

Nina is known as an excellent gynecologist, but she jeopardizes her “reputation” by performing illegal abortions and providing women with contraceptives in rural East Georgia, with its oppressive patriarchal culture. She herself leads a routine, socially isolated existence and keeps others, including her ex and colleague, at a distance. Meanwhile, she has risky, anonymous sex with men she picks up along country roads. When a newborn under her care dies, she is accused of negligence; she should have performed a caesarean section. And when a deaf-mute girl is murdered and found to have had an abortion, Nina faces a second abyss. But by then we are already nearing the end of the extremely intense April, Déa Kulumbegashvili’s second film.

Told in this way, April seems like a conventional film. Nothing could be further from the truth: Kulumbegashvili takes a more original approach. Her film is characterized by long silences and long takes. She often films events in real time. She records births in a documentary style. Nevertheless, she rehearsed with body doubles so that she and her amazing cinematographer Arseni Khachaturan knew what to do when a real birth began. And that is captured in your face, just like an oppressive abortion. Kulumbegashvili’s mise en scene is extremely effective and ‘gets inside’ the viewer. This is mainly due to the way she suggests subjectivity: with Matthew Herbert’s grinding, creaking music, for example, with the whispering, the sound of car tires, wind, and rain—all meticulously captured and edited. Paradoxically, this makes all her scenes seem “real” and at the same time extremely concentrated and controlled.

The best example: halfway through the film, a thunderstorm breaks out. In camera and editing, the filmmaker lets nature do its work in a beautiful 180-degree camera movement. Yet the image is staged: at the far edge of the shot, a car – later revealed to be Nina’s – gets stuck in the mud. And it is precisely that mud that played a decisive role in Nina’s past and probably made her who she is today to a large extent. Fiction and reality merge, as they always do in this film.

The opening of the film is intense: we see a terrifying Francis Bacon-like creature, unearthly and human at the same time. A faceless, aged body against a dark background with children playing and rain, accompanied by heavy breathing on the soundtrack. The creature appears regularly. The suggestion is that it is Nina herself. Is it the representation of her inner self? Of a transition she is going through?

Kulumbegashvili knows the area where her film is set well. She grew up there and spent a considerable amount of time in maternity clinics during the preparation phase. There she saw how pregnant women often came to consultations with their mothers. And that most of them already had six or seven children and often could neither read nor write.

This part of Georgia is an area, says one of the characters in April, “without asphalt and without paved roads.” Nina has to navigate this as a doctor, juggling the prevailing patriarchy and the law on the one hand and her professional and personal morals on the other. Should she have performed the caesarean section after all? No, she thinks, because she had to act quickly, the mother was strongly opposed to the procedure and was not known to the hospital, so there was no information about the condition of the mother and child.

At the end of the film, the pathologist gives a dry, lengthy summary of what was wrong with the stillborn child, a summary that is only understandable to doctors. The hospital’s chief physician then observes, more generally than referring to this specific case: “Perhaps God sends us hardships so that we learn to deal with despair.”

The question remains as to why the film is titled April. Is Kulumbegashvili perhaps referring to the famous opening lines of T.S. Eliot’s renowned Waste Land? “April is the cruelest month, breeding/lilacs out of the dead land, mixing/memory and desire, stirring/dull roots with spring rain.” Judging by what we see, I would say yes.

Henk Maassen

Film

Cléo de 5 à 7, back in theaters

Waiting for the results, between hope and fear

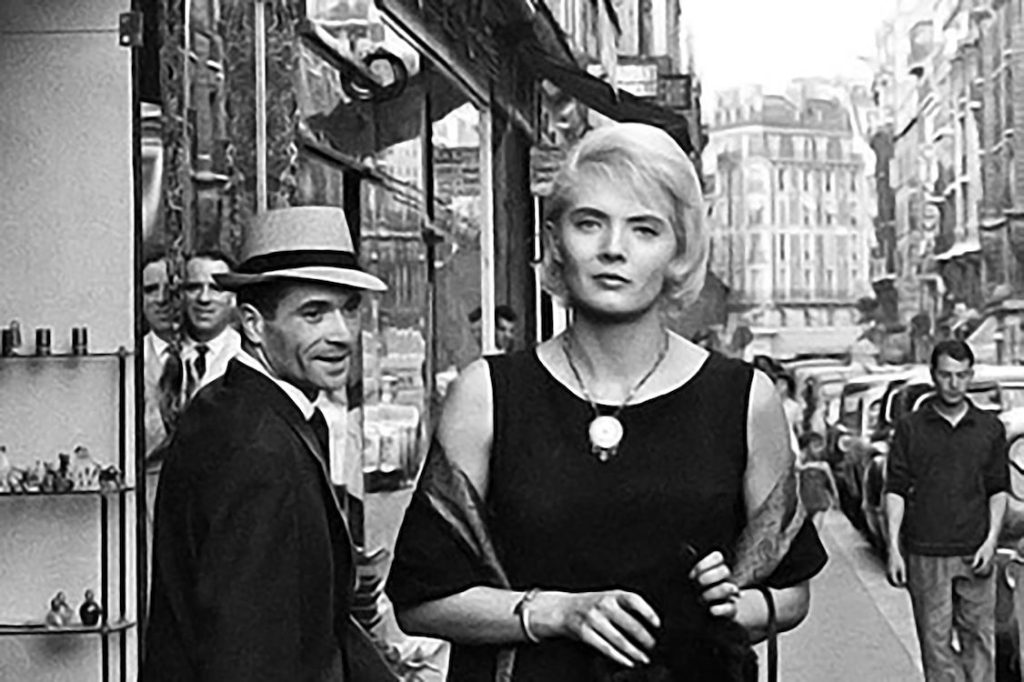

As part of a small retrospective dedicated to the great French director Agnès Varda (1928-2019), her classic Cléo de 5 à 7 (1962) is back in theaters. In this black-and-white production, we follow Cléo, a popular chansonnière, during the longest two hours of her life (from 5 to 7 in the afternoon). Two days earlier, she underwent some tests because of abdominal pain. She will receive the results at 6:30. In the film, we are with her for an hour and a half. Her own premonition, plus the prediction of a fortune teller right at the beginning of the film, do not bode well: she fears she has cancer.

Floating between hope and fear, she walks through the busy streets of Paris. The relatively restless camera—we are used to this nowadays, but in 1962 when the film was released, it was new!—seems like an independent eye that happened to catch sight of Cléo and is now following her closely. We walk with her on her odyssey from the Rue de Rivoli to the Salpetrière Hospital. And we witness her encounters in a café, a taxi ride, a visit to her apartment, and a trip to the cinema.

The objectively verifiable clock time (the film is divided into thirteen episodes) is thus suggestively contrasted with Cléo’s subjective experience of time. This makes the film less a story and more a nervous experience of time – until the moment Cléo receives the results of her medical tests.

Meanwhile, she tries to dispel any thoughts of possible physical decline and death. She thinks of the joys of her existence: ‘(…) les vacances, le reste c’est n’importe quoi.’ The world imposes itself on her, but she does not react. Neither to disturbing news on the car radio about the explosive situation in what was then French Algeria, nor to the reflection in a shop window of soldiers on their way to this colonial theater of war. Cléo is only interested in what is displayed in the shop window.

Towards the end of the film, she meets a soldier who is returning to the battle in Algeria. He convinces her that love can even take away the fear of death.

Spoiler (!): The doctor finally tells her that she does indeed have cancer, but that the disease may be curable. “Maybe I feel happy now,” she concludes. We don’t find out what she does next. If she doesn’t recover (and she won’t; Agnés Varda notes rather bluntly in her script: “Jeune femme blessé, sans doute promise à la mort.”), if her time is limited, what will her life look like? It is as if the film continues after the lights come on in the theater.

Henk Maassen